By Marvin Salomons

Changes continue to take place in the Canadian pork industry. Each year brings new threats in disease and market challenges. Even so, the industry continues to be spurred on towards opportunities fueled by primary and processing innovations that enable pork to be sought as a food of choice.

Another face of industry continues to change as well. As we delve into the barn, we see a changing culture in the people managing and caring for pigs. Not only a changing mindset but also a change in the very culture of the people themselves. Today’s Canadian pork operation is a vibrant mix of new cultures from all corners of the world. This same trend can be seen in the industries that support these farms. People with different experiences, languages and beliefs working side-by-side to produce Canadian pork for the world. The people and languages inside a barn bring a whole new dimension to working effectively in a team environment.

Visit a Canadian pork farm today and you will not be surprised to be greeted by a worker from a country other than Canada. All came by choice and desire to work in our industry. These new people bring new characteristics and are being readily embraced by the industry as a major part of a new workforce strategy and need that keeps Canada’s pork industry in the game.

Having an effective team means understanding those team members, including their cultural backgrounds. That is the message Tina Varughese brought to the 2020 Banff Pork Seminar, delivering keynotes in a breakout session called, “50 shades of beige: communicating with the cross-cultural advantage.” Rated as one of Canada’s top speakers, Varughese knows the drill. Being an Indo-Canadian daughter of first-generation East Indian parents, she draws on personal experiences in delivering her humorous, high-energy talk on diversity and inclusion in the intercultural workplace. Fifteen years of working in Alberta’s Immigration Office, in addition to operating her own settlement and relocation business in Calgary, give her a true understanding of many different cultures.

Why talk about cross-cultural communication?

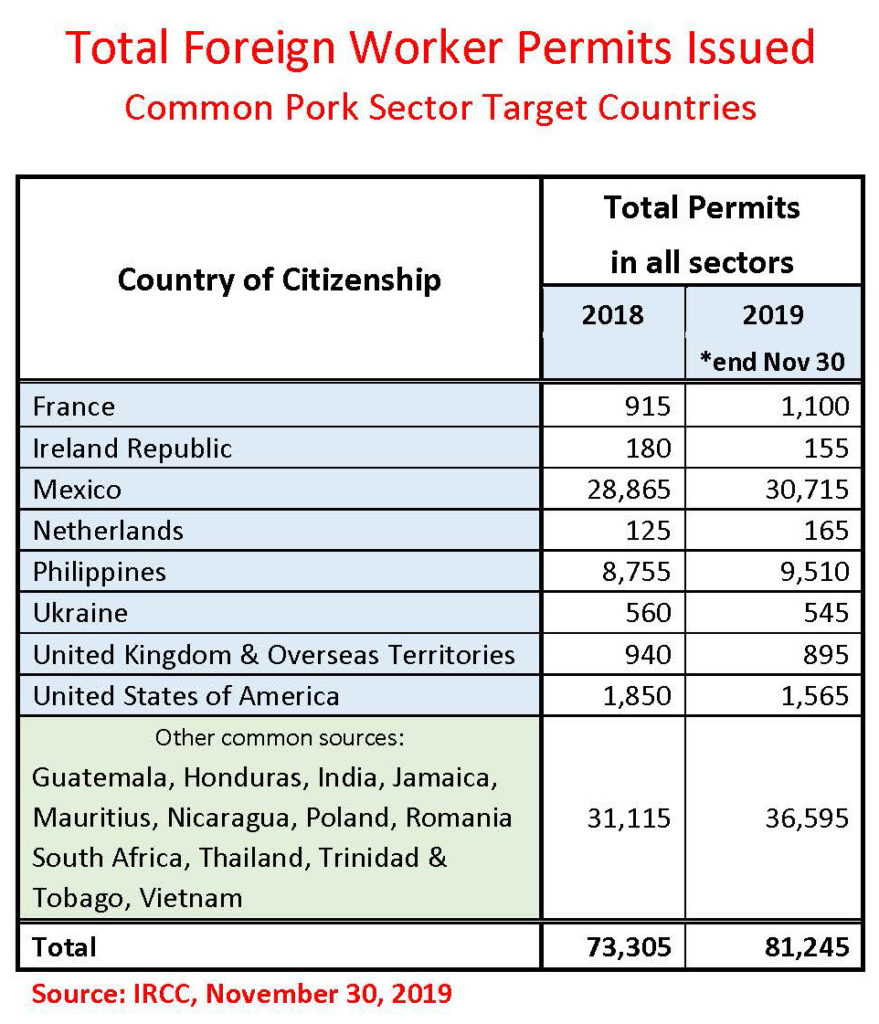

Tina Varughese says top successful organizations understand that being able to communicate cross-culturally in the workplace results in better productivity, performance and employee engagement. This is no different on the farms and businesses in Canada’s pork sector. She says managing diversity drives profitability, leads to innovation and promotes an inspiring workplace culture. Within Canada’s population, Varughese points out 20 per cent are foreign-born, with the top source immigrant countries to Canada being India, China, Pakistan and the Philippines. For the Canadian pork industry, currently, the top source countries of foreign workers are Mexico, the Philippines, the Netherlands, U.K., Ireland and Ukraine. From the industry’s perspective, there is a desire to turn these “temporary, foreign” workers into permanent Canadian residents or citizens.

Where workers originate

A view of work permits issued over the past few years by Canadian authorities show many countries provide the wide array of new cultures coming to Canada. Unfortunately, Immigration, Refugees & Citizenship Canada (IRCC) does not break down the permit numbers by sector, but historically, the most significant portion of foreign worker permits are issued to the agriculture and food processing sectors. Of those, the majority are coming under the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) from targeted Caribbean countries and Mexico for seasonal businesses like beekeeping, fruits, vegetables, tree nurseries and other harvesting operations. While IRCC data covers all Canadian business sectors, the countries of origin represented in the pork sector do represent a significant portion of the foreign worker permits issued in agriculture each year.

Individualists versus collectivists

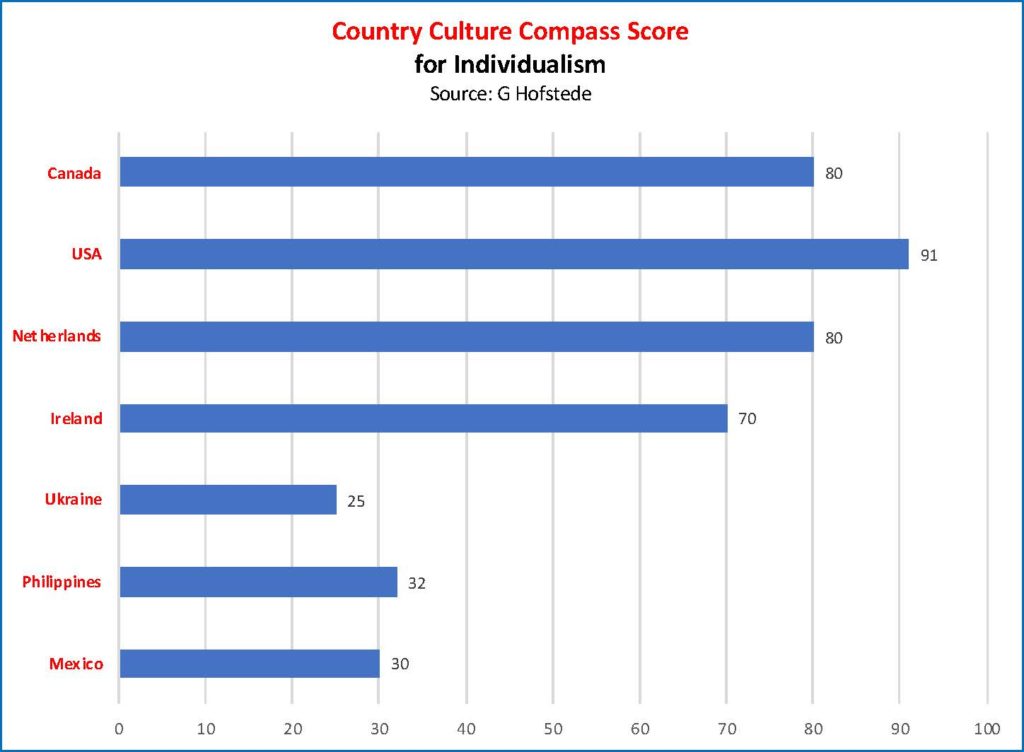

From one country to another, our appearances may differ, but so do our values and approaches to interpersonal interactions. Varughese’s message builds on this using the work of renowned Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede, well-known for his pioneering research on cross-cultural groups and organizations. The concept centres around findings that show, depending on the society in which a person is raised, he or she will either lean towards individualism or collectivism.

Varughese says individualist values reflect individual tastes, goals, achievements and accomplishments, whereas collectivist values reflect shared ideas among families, work divisions and communities. Every decision, conversation and contribution we see in the workplace is reflected by these constructs. According to Hofstede, it has to do with whether a person’s self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “we.” In individualist societies, people tend to look after themselves and their direct family only. In collectivist societies, people belong to “in-groups” that take care of them in exchange for loyalty.

Considering the cultural compass of pork farm workers

If managed well, diverse teams work. Knowing the team’s individual make-up and values is key. Hofstede developed his “culture compass” around six values – one of which is the degree of individualism inherent to a society and how this is reflected by those who belong to that culture.

Hofstede’s compass scores each country on various traits. The top collectivist countries in the world are Guatemala, Ecuador, Panama, Venezuela, Columbia and Indonesia, while the top individualist countries are the U.S., Australia, U.K., the Netherlands, Hungary and Canada.

In looking at several of the main countries used to source foreign workers for the pork industry, we can see huge differences in country scores based on Hofstede’s compass. Comparing several selected countries like Mexico, Ukraine and Ireland with Canada demonstrates why it is important for employers to consider this information when dealing with foreign employees.

Mexico, with a score of 30, is considered a collectivist society. For Mexican workers, loyalty is paramount and overrides most other societal expectations. Mexican society favours strong relationships where everyone takes responsibility for fellow members of their group. In collectivist societies, an offence made to someone often leads to shame and loss of face. In addition, employer-employee relationships are perceived in moral terms, much like a family link. While Canadians may not instinctively think along these lines, employers hiring and promoting workers from collectivist cultures should take into account how these decisions could affect an employee’s in-group.

Ukrainians are also found to be very collectivist. If Ukrainians plan to go out with their friends, they might say, “We with friends,” instead of, “My friends and I.” Family, friends and even entire neighborhoods are foundational to Ukrainians’ approach to everyday life. Relationships are crucial for obtaining information, social networking or for successful negotiations. They need to be personal, authentic and trustful before one can focus on tasks and build on a communication style.

Canada and the U.S. score 80 and 91, respectively, on the dimension of individualism. These figures are the highest for this given dimension, characterizing us as having as very individualist cultures. In the business and working world, this translates into an employee expectation of self-reliance and initiative. Within the exchange-based world of work, hiring and promotion decisions are based on merit or evidence of what one has done or can do. As a result, a Canadian individualist working alongside a strong collectivist will approach communication and the job quite differently.

Communicating using different styles

In her presentation, Varughese pointed out there are several communication styles that are factors in how people talk and deal with each other. She elaborated on the following categories:

Reflexive: Reflexive communicators will often repeat parts of the conversation using the same tone and intonation in the conversation. Reflexive speakers feel repeating the conversation shows respect and understanding.

Interruptive: Interruptive communicators often interrupt the conversation without knowing it. Given their family and community-oriented culture, collectivists are often by nature interruptive.

Direct: Direct communicators use fewer words and less non-verbal communication. This practice may be perceived as rude, abrasive or arrogant, but in reality, it may be indicative of culture. Like many North Americans, Ukrainians are very direct communicators and may not need as much positive reinforcement as others.

Indirect: Indirect communicators are often collectivists who view group or team harmony as being more important than disagreeing with someone. Mexicans who fall within this group are less direct in communication. Filipinos are strong collectivists, very hierarchal and indirect communicators. For them, saving face is important, so careful, non-embarrassing feedback is key.

The methods by which employers communicate with employees can have a significant impact on job performance. Varughese says there is a close link between performance feedback and indirect versus direct communicators. In North American cultures, she says the “sandwich approach” is used to offer performance feedback. The process involves delivering positive news first, followed by constructive criticism and ending with positive feedback. However, not all cultures resonate with this technique, but employees from all cultures still need meaningful feedback. Offering specific positive feedback will reinforce desirable behaviour. An employer could try saying something like, “You did a great job processing that last batch of pigs. It was done right, fast and met our SOPs.”

Varughese says direct communicators do not always give positive feedback, as it is not part of their culture, and doing good work is viewed as an expectation. She says this can be deflating for some and lead to employee disengagement on the job. She notes indirect communicators still need positive feedback, but if they are collectivists, the praise would be better offered in-person rather than in a group setting like the staff room at coffee break. In this case, indirect communicators will not respond well if the entire team is present. The feedback is better delivered behind closed doors so that the indirect communicator, who may also be a collectivist, recognizes that their job is not threatened. Hierarchy is important in some cultures and can play a role in the process.

Communicating using different platforms

In today’s workplace, communication is typically done in one of three ways: face-to-face, by phone or by email. In the pig barn, communication within and between teams or management can be difficult especially where technology is not readily accessible or where differences in culture, language or understanding of expectations are unclear. In collectivist cultures, like Mexico and the Philippines, chit-chat is about relationship-building and may include discussion about family, community, school, politics and sports. On the other end of the spectrum, in Canada, chit-chat can be superficial and addresses the current weather or asking how someone is feeling, often without much emphasis on finding out the true answer.

Language skills are important in relaying your message, especially when it comes to doing important tasks on the farm, such as breeding sows, recording data and identifying health concerns. Varughese says, if English is a second language, a phone call should be followed up with an email, to ensure the message is understood and that nothing has been lost in translation. Another technique is the use of photos as a communication aid, if the matter is visual in nature, such as animal health symptoms. Using this technique can also spare workers from embarrassment or misunderstanding if accented speech is an issue.

Varughese also notes where mixed cultures and languages exist in a working team, speaking only English or French on the job should be encouraged. This alleviates issues where people feel they are being excluded from the conversation or being talked about. In some cultures, this can be viewed as rude. Leave the talking in mother tongues for coffee and lunch breaks.

Exercise caution with non-verbal communication

According to Varughese, non-verbal communication such as gestures, posture, eye contact, smell, silence and personal space can be interpreted differently in each culture. Gestures such as physical greetings – like handshakes, hugs and kisses – vary from culture to culture, and simple signs such as giving the “thumbs-up” or the “all-OK” sign can mean different things and might be considered offensive in some cases.

In North American culture, direct eye contact is expected and respected, while in some cultures, it can be viewed as disrespectful. Vocal tone and volume can also be perceived differently. Some cultures expect leaders to have loud voices; on the other hand, in Japanese culture, a loud voice signals someone is out of control. In North America, silence is often viewed as a lack of interest, whereas in some cultures, it is seen as someone who is reflecting on what is being said.

Opening your mind will help your operation

Navigating the ins and outs of cross-cultural communication may be daunting, but it could also be an important consideration for your business. Rather than arriving at wrong conclusions about your workers, try to understand their backgrounds and how this affects communication.

To wrap up her presentation, Varughese asked attendees to rise from their seats and participate in a fun dance routine based on the Bollywood-style of Indian movies. The exercise was done to demonstrate a principle: when in doubt, mirror the image, the gesture or even the tone when dealing and communicating with employees whose cultural backgrounds are different from yours. Failing to do so could result in lost production or profit.