By Andrew Heck

Disease speads fast; news, even faster

January 8, 2019: as Alberta Pork’s communications coordinator (but not yet editor of the Canadian Hog Journal), I showed up to the Alberta Pork office in Edmonton in the morning, overnight bag in-hand, ready to gather with two colleagues, load up the vehicle, and head to the Banff Pork Seminar. There was just one problem: Alberta had discovered its first-ever case of porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) at a 400-head farrow-to-finish operation.

Immediately, the focus quickly turned from a relaxing four-hour drive to a pressing need for communicating what we knew about the outbreak, which was little, other than a confirmation of the virus’s presence. PED is a provincially reportable disease, meaning it would not have been long before the public caught wind of the news through one channel or another. In the interest of prudence and transparency, Alberta Pork wanted to get ahead of any potential rumours or misinformation.

After receiving the basic details of the incident, I hammered out a news release, posted it to the Alberta Pork website, and made my way to Banff alone, as our Quality Assurance and Production Team (Javier Bahamon and Cris Neva) stayed behind to assist incident command efforts alongside government officials, including visiting the affected farm to support the producer during that time of extreme difficulty.

By the time I had arrived in Banff, the PED case was already the talk of the seminar. Social media has a way of moving quicker than a truck on the highway. And while PED first entered Canada from the U.S. in 2014, it was unclear exactly how PED made it to Alberta from eastern Canada in 2019. And now, two years and three more PED-positive cases later, ‘presumptive negative’ status has been granted to all four previously affected farms, thanks to the hard work of so many people in the industry to stem the spread.

But a bigger question still remains: how did it happen?

Alberta Pork’s environmental disease surveillance program is always on guard to protect the industry, performing thousands of routine tests annually with the cooperation of farms, assembly yards, processing facilities and truck washes. While theories exist, Alberta’s 2019 PED cases still have uncertain origins, despite intense investigation – such is the nature of this incredibly complex problem. Many have speculated that porcine plasma is likeliest culprit, though this has never been confirmed.

Viruses move through contaminated feed

At the 2021 Banff Pork Seminar, Scott Dee of Minnesota-based Pipestone Veterinary Services presented, “Feed biosecurity: the new normal for North American agriculture.” Prior to May 2013, when PED first entered the U.S., feed ingredients were largely overlooked as potential vectors for pathogens to spread. The link between swine diets and disease has been further investigated over time to take a specific look at PED and African Swine Fever (ASF).

Experimental data collected by Pipestone’s researchers, led by Dee, has demonstrated that some feed ingredients can support the viability of pathogens. After PED started to spread in the U.S., three separate farms in the states of Minnesota, South Dakota and Iowa – clients of Pipestone – experienced simultaneous outbreaks. It was determined that feed bins on all three farms had been refilled at the same time, using the same supplier, and by the time that refilled feed was consumed by the respective farms’ sows, PED was quick to follow. It was this finding that prompted a deeper dive – for real.

“I was literally leaning over the feed bin with a long pole and a paint roller, and I was scraping the inside, collecting that feed material,” Dee recalled. “We brought it over to South Dakota State University and fed it to pigs. They consumed it, and within three or four days, they had clinical signs of PED virus.”

Dee’s test resulted in the first known demonstration of how PED could be transmitted to pigs through feed. More recently, in the case of ASF, virus survival has been successfully confirmed in nine distinct animal and human foods, including three soy products, choline chloride, three pet diets, pork sausage casing and complete feed exported from China to the U.S.

When ASF was discovered in China in 2018, contaminated food scraps imported from Russia were to blame, as this waste was bought cheaply by Chinese producers and fed to pigs. The issues inherent to feeding food scraps to pigs were covered in the Winter 2021 edition of the Canadian Hog Journal: “Feeding scraps is no solution to food waste.” From contaminated food scraps, farm-to-farm transmission of ASF was swift.

As a result of ASF, based on varying reports, China’s sow herd was reduced by nearly one-half between late 2018 and early 2020, but the Chinese hog industry has been bouncing back, with special considerations given to feed. In response, the Chinese government has since banned feeding human food scraps to pigs, and conventional feed ingredients are now being handled with greater caution.

“Nobody really knows how many sows there are in China, but clearly there’s a rapid growth of the national herd. It’s big bucks,” said Dee. “About the feed risk, the Chinese are very concerned. Everything’s pelleted in China. They put feed through an extensive heating process by cooking it at 85 degrees Celsius for three minutes before the pellets are used.”

Not all feed ingredients are equal

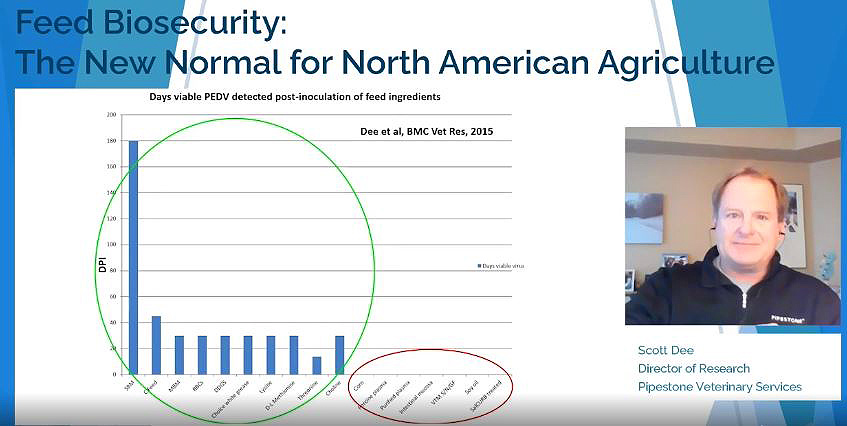

Turning their attention to specific feed ingredients, Pipestone researchers decided to measure ingredient survival times and noted a stark difference between most ingredients tested and one which stood out: soybean meal.

“We held the ingredients outside in January, in Minnesota, so it was very cold,” said Dee. “We sampled them monthly, and in a handful of ingredients, we found live virus over time.”

According to the test results, live PED virus was detected in soybean meal more than 180 days later, whereas the virus had disappeared in most other tested ingredients within only 40 days. The soybean meal results suggest that surviving a hypothetical transcontinental journey from China is more than possible – in fact, quite likely.

This discovery led the researchers to think harder about how grain-drying practices in Asia could contribute to the contamination of feed. Much of that grain-drying, prior to ASF, was being performed in the open air, using traffic from people and motor vehicles to crush the grain and encourage moisture evaporation, along with the unintended consequence of disease transmission. Recognizing that this practice may have been responsible for helping spread ASF, Chinese officials have since tried to streamline and sanitize the process using modern facilities with strict biosecurity protocols, including Danish-entry-style precautions.

In 2018 and 2019, three-quarters of U.S. soymeal imports came from China, Ukraine and Russia – all three of which are ASF-positive countries. By 2020, that number had declined, but the U.S. imports close to 500,000 tonnes of soymeal annually, while exporting a staggering 50 million tonnes of its own. Though the massive discrepancy is not necessarily surprising to market analysts, it might alarm producers and other industry partners to know.

“It’s like a teeny, little needle in the haystack. It’s silly we even have to deal with that,” said Dee. “But that’s the way things work these days in global trade. So that’s crazy, when you think about it.”

Soy it ain’t so

From human food scraps as pig feed to soy-based goods for human consumption, products containing phytoestrogens, including soy products, are suspected of potentially leading to gradual hormonal imbalance in those who eat them in excess. As such, the reputation of soy used in human food has taken a hit over time, as consumers become more discerning with their choices.

Could soy imported for human food possess the same risks as soy imported for pig feed? Dee draws no distinction between the soy format – only its origin.

“The risk of soy is independent of whether it comes in for animal feed or human food,” said Dee. “The product is a vehicle to bring the virus into a country.”

According to the Good Food Institute – a U.S.-based non-profit that supports plant-based businesses – upwards of 79 per cent of soy protein isolate, 50 per cent of textured soy protein and 23 per cent of soy protein concentrate used worldwide is sourced from China.

According to Nielsen – the Canadian-based global measurement and data analytics company – the meat and dairy alternative market in Canada was up by 31 per cent in value in 2020, worth nearly $300 million. The largest single player in that space, Yves Veggie Cuisine, was founded in 1985 to satisfy a “growing demand for healthy, ethical plant-based products.” Yves’ lineup of nearly 50 separate offerings includes mostly simulated meat products using textured soy protein as the dominant ingredient. Yves’ website does not disclose ingredient sourcing, apart from indicating that products are manufactured in Canada using domestic and imported ingredients.

“Although ingredients are predominantly sourced domestically, it is sometimes necessary to source globally,” an Yves product specialist wrote in an emailed response. “This is due to the fact that some ingredients are not available domestically or the domestic sources are limited based on market demand.”

Could the import of foreign soy for human food similarly risk the Canadian livestock industry simply by its presence in the country? Canadian soybean meal imports have hovered around one million tonnes annually in recent years and peaked at more than 1.5 million tonnes in 2007, while the use of soy in human food products has steadily risen since then. Understanding what is driving this demand in either the animal or human food sectors is important.

Buyer beware – biosecurity matters

Can biosecurity guarantee a disease-free farm? No, but it can help reduce the risk. Biosecurity, together with understanding where feed ingredients are sourced, can help producers protect themselves against what looks to be a growing threat to animal health around the world.

Across Canada, feed ingredient composition varies, but Canadian pork is noted in lucrative markets globally for having a distinctive profile that comes from the inclusion of barley and wheat in diets. Corn and soy may be more widely available and less expensive in some regions, but when soy especially has its origins in ASF-affected countries like China, this should be a red flag for producers to pay closer attention.

Even the strictest biosecurity can still result in disease incursions within a herd, but it is better to be safe than sorry. Feed tops the lists of costs for producers today, and saving money in that area may appear compelling. An increasing cost of production, together with reduced revenue, has been a crippling barrier for many Canadian producers in recent years, and industry stakeholders must work together to ensure the long-term sustainability of the sector, which includes protection against disease. Recognizing the cost of that work will be important for everyone to consider and act upon.