By Dan Columbus & Jade Sands

Editor’s note: Dan Columbus is a research scientist at Prairie Swine Centre. He can be contacted at dan.columbus@usask.ca. Jade Sands is a former research assistant at Prairie Swine Centre.

Creep feeding is a common practice throughout the pork industry with many perceived benefits, including provision of nutrients, higher weaning weight and improved transition at weaning; however, these benefits only occur if the creep feed is consumed.

It is estimated somewhere between four and 40 per cent of piglets will consume creep feed during lactation.Intake of creep feed is usually low and highly variable among pigs, with smaller piglets having higher intake and larger piglets having little to no consumption. The achieved benefit of creep feeding on growth performance in the lactation and nursery period remains inconsistent.

The benefits of providing creep feed may have less to do with provision of nutrients and more to do with exposing piglets to a dry feed and enhancing exploratory behaviour. Dietary diversity, such as particle size variation, has been shown to have a greater influence on pre-weaning feed intake than dietary flavour. Therefore, it is possible that provision of expensive creep diets is not necessary to achieve creep feeding benefits related to weaning weight and overall performance. Feeding simple diets, such as a typical lactation diet, may be sufficient. Identifying less expensive alternatives will help to reduce cost of production in the pork industry.

Methodology

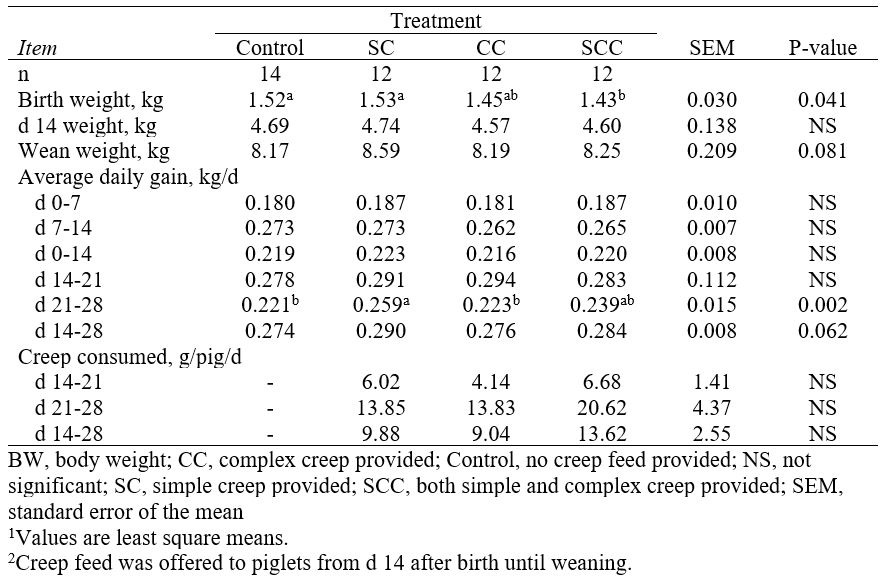

A total of 50 sows and litters with between 12 and 14 piglets per treatment were randomly assigned to one of four creep feeding treatment protocols. The protocols were:

- No creep feed provided

- Complex creep feed provided

- Simple creep feed provided

- Combination of complex and simple creep feed provided

The complex creep consisted of a standard nursery starter diet, and the simple creep consisted of a standard lactation diet. For the combined treatment, one feeder contained the complex creep and one contained the simple creep.

Sows were moved into the farrowing room approximately five days prior to the expected farrowing date and placed on a commercial lactation feed. Upon farrowing, total pigs born alive and litter weight were recorded. Within a day of farrowing, piglets were cross-fostered, if needed, equalizing the number of piglets per sow.

Litter weight was recorded weekly on the seventh, 14th and 21st days. On the 28th day, at weaning, all mortalities were recorded and litter size was adjusted. On the 14th day post-farrowing, litters were placed on their respective creep protocol treatment. The type of creep provided and intake were recorded daily and adjusted for wastage. Fresh creep feed was provided each day until weaning.

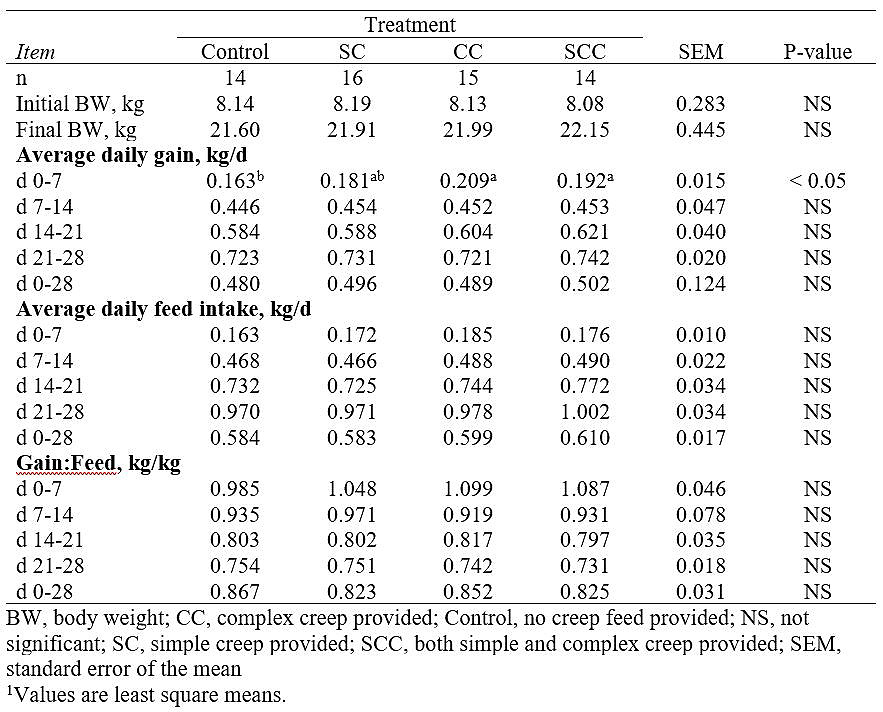

Upon weaning, piglets were housed in pens of 10 to 13 pigs per pen, with each treatment having 14 to 16 pens within pre-weaning treatment groups. Individual pig body weight and feed intake per pen were recorded weekly for four weeks.

Results

There was no difference in litter performance prior to provision of creep feed or in average daily gain throughout the first week after creep was provided. However, the second week saw an increase in average daily gain in piglets, with an overall trend for improvement in litters receiving the simple and combined creep treatments. There was no difference in creep feed intake across treatments. There was no preference for simple or complex feed (Figure 1) in piglets that had access to both dietary treatments.

Overall, there appears to be little benefit to providing creep feed under the conditions of the current study. It should be noted, however, that the data represents averages by litter (or pen), which does not account for potential positive effects of creep feed on individual piglets. Previous work has indicated there may be a benefit of providing creep feed but only in those piglets that actually consume it.

Another factor to consider: while creep feed had no benefit on overall pig growth, there may be other benefits that were not determined in this study. For example, quicker adaptation to feeding and adjustment to plant-based diets versus milk may help to improve gut development and health, improving long-term robustness of the pig. Future work should focus on the non-growth impact of creep feeding.

Results indicate piglets had no preference between the simple or complex creep diets. Intake of both creep types was similar in the group that had access to both diet types.

Conclusions

This study has shown how providing creep feed has little impact on pre-weaning performance, with increased average daily gain only in the final week pre-weaning. While there was a slight benefit to providing creep feed on growth performance in the first week post-weaning, this was not maintained through the nursery period.

Overall, there appears to be little benefit of providing creep feed in general or of providing complex, expensive creep feed. Further research is required to determine the impact of creep feed on individual pigs and to determine if increasing the number of pigs consuming creep feed will create potential benefits.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the Government of Saskatchewan through the Agricultural Demonstration of Practices and Technologies program. General program funding for Prairie Swine Centre is provided by the Government of Saskatchewan, Sask Pork, Alberta Pork, Manitoba Pork and Ontario Pork. Assistance provided by Prairie Swine Centre staff is gratefully recognized.