By Andrew Heck

Rocky starts lead to hardened legacies

Many roads (and rails) lead to Banff (and the Banff Pork Seminar), when it comes to transport corridors, frontier settlement and agriculture industry development.

As the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) reached the Bow Valley of the Rocky Mountains, in 1883, workers discovered natural hot springs on the side of Sulphur Mountain. The next year, CPR president George Stephen named the stop on the rail line ‘Banff,’ after his birthplace in Scotland. Rather quickly, CPR executives had a lightbulb moment and saw a bold vision for the entire area.

From the very beginning, the railway and Banff have been intimately connected. Not long after the station was built, CPR took the opportunity to commission the construction of the original Banff Springs Hotel, in 1888, and the site quickly grew into Canada’s best-known mountain destination, bringing in guests from across the country and around the world.

There is no denying that Banff is an exceptional tourist destination, but Canadian transportation history is even more important for Canadian agriculture. Tourism across Canada today generates approximately $40 billion in annual federal revenue, while agriculture comes in at a whopping $140 billion, for comparison. This is thanks mainly to farmers from coast-to-coast who produce crop and livestock commodities, many of which eventually make their way to the Port of Vancouver to be shipped across the Pacific Ocean to Asian marketplaces.

But before they get there, these high-value goods must traverse a forbidding alpine landscape, whether by truck or train. The paths carved through the wilderness over the years cost many millions of dollars but also thousands of lives. It is a legacy of triumph and tragedy that we would do well to remember, for both the good and the bad.

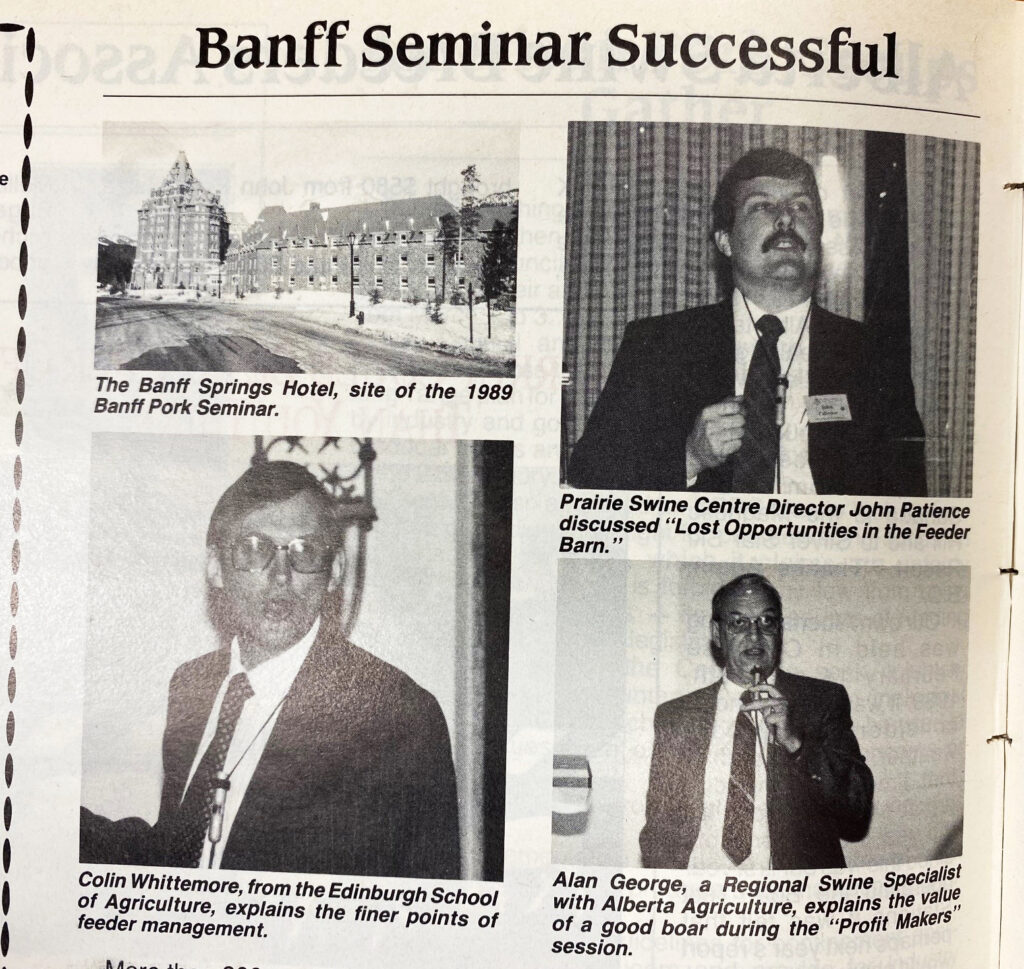

The industry begins its ascent

Fast forward to 1972. The Banff Pork Seminar’s roots were laid in Olds, Alberta, northwest of Calgary, where Olds College – a respected agricultural technical institute since 1913 – hosted the first version of the event, with the cooperation of Alberta Pork, the Government of Alberta and the University of Alberta. These long-time partners are still intimately involved today. This year, the Banff Pork Seminar officially reached its half-century milestone, inspiring the advisory committee to settle on the theme, ’50 Years of Knowledge and Sharing.’

Normally, the seminar attracts upwards of 800 guests, but this year, only about 200 individuals were welcomed in-person and 400 virtually. Not bad, considering that the spread of the COVID-19 Omicron variant seriously jeopardized the event’s status right up until two weeks before a final commitment was made to move forward with the in-person and virtual hybrid concept. It is the first major pork conference to take place this way in Canada since the start of the pandemic.

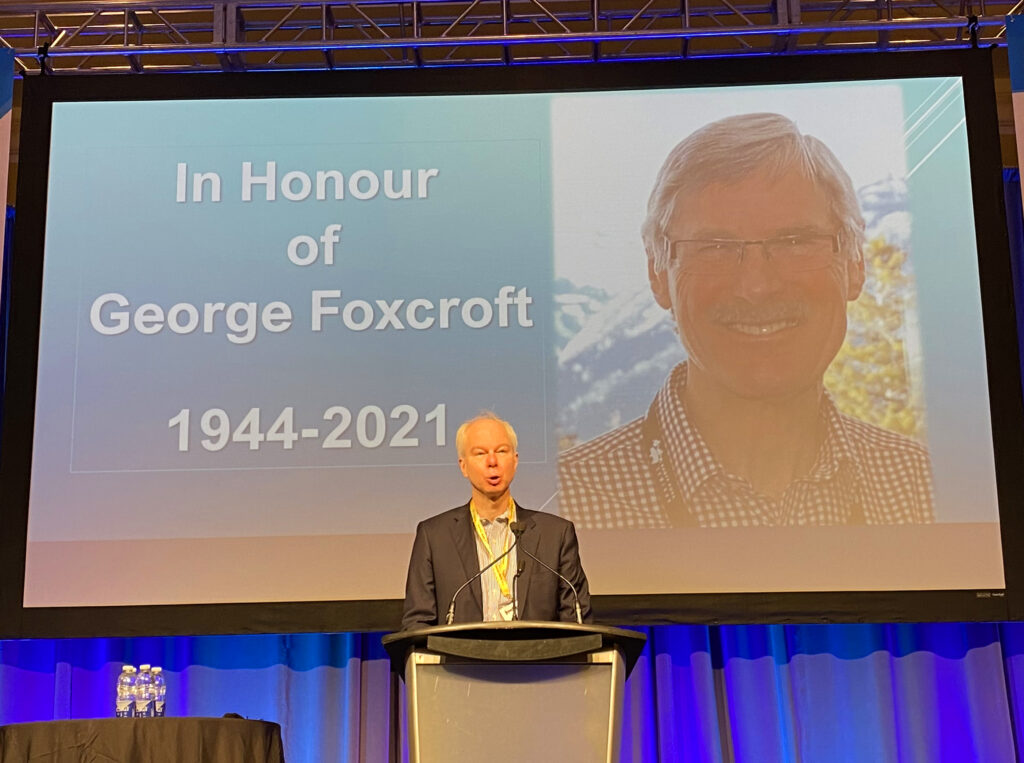

Research has always been the driving force behind the seminar. In 1988, a now-legendary man named George Foxcroft was sponsored by Alberta Pork to move to Canada from the U.K. as a research chair at the University of Alberta. He led the Swine Reproduction-Development Program there until his retirement, in 2012, when he became a professor emeritus.

“George was a global leader in the field of regulating ovarian function and early pregnancy loss, and he was the Canadian authority in understanding reproductive physiology of the pig,” said Ruurd Zijlstra, a researcher at the University of Alberta who has long been involved with the seminar. “Throughout his research career, George focused on maintaining a two-way dialogue with the industry to understand their problems and success. His goal was always to ‘bring research to reality.’”

Each year, Foxcroft’s legacy is honoured during the Banff Pork Seminar with the ‘George R. Foxcroft Lectureship in Swine Production.’ This year was the first time the lectureship was awarded by someone other than Foxcroft himself, after he unexpectedly passed away just over a month before the seminar. The lectureship was established in 2013 to recognize outstanding international pork industry representatives and cover their costs to attend and present at the event. Foxcroft will be truly missed, but his legacy as a leader in the Canadian pork industry will endure.

Canadian pig science and pork trade emerge

Now, flash way back to the early 17th century. According to Trevor Sears, President & CEO, Canada Pork, who presented during the first plenary session of the 2022 Banff Pork Seminar, pigs first arrived in New France (today’s province of Nova Scotia) with settlers who brought the animals to be raised and consumed as a convenient source of sustenance. It took 200 more years, until the mid-19th century, when Canadian domestic pork trade finally took off.

Eastern Canada was already thoroughly inhabited by this time, and to satisfy a growing demand for meat not only in Canada but also in Britain and the U.S., pork packing plants began popping up in the cities surrounding the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River, earning Toronto the nickname ‘Hogtown.’ This period of time marks the beginning of Canadian international pork trade.

At the same time, settlement in western Canada was actively starting to take place, largely aided by railway expansion. The same infrastructure development that brought people westward would become responsible for enabling a large part of the export system that exists today, with 70 per cent of Canadian pigs and pork ending up in foreign countries. As with many other agricultural commodities in Canada, this globalized reality is the backbone of our commercial industry.

In 1947, the first-ever Canadian-developed hog, the Lacombe breed, was registered as a cross between Landrace, Berkshire and Chester White varieties, treasured for its suitability to the Canadian climate. The breed was created at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Lacombe Research and Development Centre in Alberta, southeast of Edmonton. The breed’s development was spearheaded by Howard Fredeen – another industry titan who sadly passed away in the week leading up to this year’s Banff Pork Seminar. Like Foxcroft, Fredeen is lost but will not be forgotten.

Domestic and international markets continued to grow throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and by the 1980s, hog farming reached its peak across Canada. Starting in the 2000s, the number of hog farms started to decline dramatically, but production steadily increased. It is a common trend throughout the world of commercial livestock, and it defines our sector today.

Two Banffs but only one Banff Pork Seminar

When CPR president George Stephen decided to name his new western Canadian train stop after his Scottish hometown, it is hard to say whether he knew the settlement would one day eclipse its namesake in terms of recognition and importance to commerce.

Less than a century later, the Banff Pork Seminar would leverage that reputation and blossom into Canada’s best-known pork conference, having carved-in-stone a significant chronological milestone of its own. History has an interesting way of playing out.

Other jurisdictions all over the world raise pigs, process pork and perform important research and extension activities that benefit the global swine sector. Many of these jurisdictions are more populous, more productive by total volume and just as proud of their accomplishments as we are of ours. But the fact remains: there may be two Banffs, but there is only one Banff Pork Seminar.