By Stewart Skinner

Editor’s note: Stewart Skinner is a hog farmer near Listowel, Ontario – about 150 kilometres west of Toronto. His article is a response to Lesley Kelly’s presentation during the ‘Human Resources’ breakout session at the 2022 Banff Pork Seminar. Skinner and Kelly are partners with the ‘Do More Agriculture Foundation’: champions for the mental well-being of all Canadian producers.

With every sunset starting a little later and lasting a little longer, we Canadians can start to anticipate the conclusion of another winter. While much of the art in our vocation has been altered by technology, there is still the rhythm of the seasons that every farmer must dance to, and spring is the favourite time of year for most.

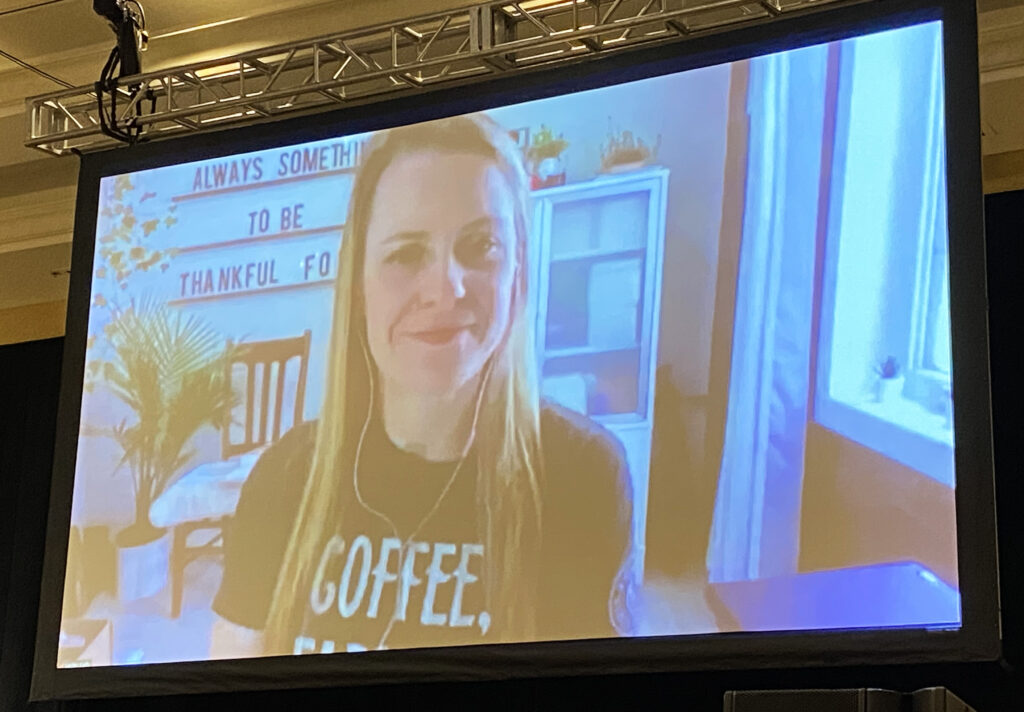

We emerge from our barns and sheds for the promise of another year and the hope of a bountiful crop ahead. Sadly, every year there are a few of our brethren that do not join us again – friends that succumb to a disease continuing to stalk farmers across Canada. Mental illness is no stranger to farmers, and, tragically, it continues to collect a heavy toll.

I first shared publicly about my struggles with depression and anxiety in 2013. Today, we are in an entirely different world; long-held stigmas that led to widespread repression of healthy outcomes for those who deal with mental illness are now in the rear-view mirror. Awareness among the general population is as high as it has ever been, following a watershed change in how the disease itself is viewed over the past decade. No longer do people ‘kill themselves’ – they die of suicide after battling a deadly disease. This positive environment means more people feel safe to get out of their own shells and seek help, whether it be traditional therapy, medication or alternative treatments like music or art therapy.

Awareness has never been higher, but why are we not making progress on the farmer suicide front?

As a person who has lived with this for some time, there is very much an ebb and flow to how healthy my mind can be. Mental health is not a light switch – on and we are fine, off and all is dark and sad. It is dynamic and ever-changing. Think of standing at the shore of the ocean; there are times of calm and times of uncertainty, the impact of which can depend on the tide itself. Picture the oncoming storm on the horizon; if the tide is out, those crashing waves can do less harm. Such is the case with our mental resilience. The impact of an unexpected calamity is dependent on the underlying health going into the crisis. A person who has a high degree of resilience has a better chance of living through the storm than someone who is already mentally exhausted prior to impact.

Over the past two years, I have watched the model I constructed to keep my resilience up be torn apart, ironically in the name of keeping me safe.

Due to poor first experiences with the field of psychiatry, I have always been skeptical of how most doctors approached mental health, given the heavy reliance on medication versus the basket of different therapies that have been developed. My resilience was buffered through communities – friends and colleagues that I could share with, recreational sports and my church. There were also unhealthy coping mechanisms present – alcohol and cannabis – yet on the whole, there was stability that came largely through community support.

Since the start of COVID-19, each of those healthy pillars has been taken away for at least some part of it, and in the case of sports, I have not bricked a three-point shot since our last basketball game, in January 2020. Conversely, while my church was closed and I could not meet a fellow hog farmer for breakfast at the greasy spoon in town, the lights never turned off at the beer store, and my body has now become fully addicted. It takes serious concentration to make it through a day without cracking a beer out of habit.

My partner, Jessica, and I founded Imani Farms, in 2015, when we purchased a sow herd from my parents. Over the years, we have experienced success and have been able to grow that into a business that focuses on niche markets like ‘Certified Organic’ and ‘Certified Humane’ for customers in Canada and the U.S. We entered into those markets to seek out value chains that removed the volatility of the traditional pig market. That said, we both grew up in pig farming families and understood the realities of the pig business.

2021 was a good reminder that, no matter the market you are in, pigs need to move on time, and you need to keep animals healthy. 2021 saw shipments come to a grinding halt mid-year, as COVID-19 wreaked havoc on Canadian meatpacking plants. Health has suffered, as we had a number of disease issues throughout the year – no small thing in a production system for which any antibiotics must be administered on an individual level. Add in soaring feed costs for good measure, and we had quite the tempest brewing. Now remember the previous analogy – that tempest hit when the tidewaters were already lapping at the pier. As wave after wave hit, my condition eroded further and further. There were two specific 48-hour periods last year when suicide was as close for me as ever, with a mind desperate to escape the pain and only a mental image of a loving partner and two beautiful children to shine through an inky darkness.

2021 has likely made me a better farmer; however, it has made me much more cynical about the progress we have seen on the mental health front. One cannot deny the importance of awareness – these words do not get printed on these pages in decades past. Yet, how much of that awareness was generated from a genuine place and not just a shrewd method to improve a corporate or personal image?

I say that I have become cynical, because I have learned over the past 12 months that if my personal story challenges the worldview of another, that person is more apt to dismiss my experience than actually listen and learn. Perhaps, they get uncomfortable. At the root of my newfound cynicism is that farmers are still dying from mental health issues, and the people with the power to change it are only interested in ensuring that they do the bare minimum to justify a couple hashtag-laden tweets on certain days of the year. 2021 was the year it became apparent to me that our politicians view farmer suicide no different than national expenditures on fertilizer – just another line item on the income statement.

Friends, things are not fine. I have hog farming friends who, by the time this hits your mailbox, will no longer have a hook for their pigs. We are about to enter a farming season during which we can no longer assume that the part we need to finish the job before the rain hits will be at the dealership. We have federal regulations that are quickly becoming out-of-step with our global competitors. We have uncertain times, with the price of farmland skyrocketing once again and high interest rates lurking just around the corner. All of the factors that make farming one of the most stressful occupations are inflamed. Things are not fine.

Is all lost? Should we throw up our hands and be happy that at least we have created a society in which we celebrate those who seek help versus belittle?

Personally, I would like to move from being a line item and instead be classified as an intangible asset. We can start by tearing down the silos that dominate the traditional healthcare field, and as a country, we can decide saving farmers’ lives today is more important than haggling over jurisdiction or who is paying for what.

There is an urgent need for a national, bilingual, 24/7 crisis line that is available to every farmer from Comox to Codroy, staffed with professionals that have been trained specifically to deal with farmers – the type of people who know it is a bad idea to tell a farmer to ‘just take a break’ at the height of the busy season. Beyond that, the need is no different for the more than seven million other Canadians who deal with mental illness – a national pharmacare system so that financial standing does not get in the way of finding the right medication and improved accessibility to therapy.

The farmer is the lynch pin of Canada’s largest industry, which employs more Canadians than any other already, while having the potential to continue growing. There are less than half a million of us left in Canada, and the institutional knowledge in our collective hive mind is what will ensure each year there are dancers ready to hit the field when mother nature starts playing her springtime tune. One could argue we are a resource worth protecting.