By Bijon Brown

Editor’s note: Bijon Brown is the Production Economist for Alberta Pork. He can be contacted at bijon.brown@albertapork.com.

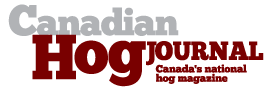

High feed prices seen today have resulted from a combination of local and global events. By understanding some of the major factors that are currently affecting feed supplies and pricing, risk mitigation may be possible.

From the war in Ukraine, to moisture conditions across the Americas, to international trade relationships, feed prices have remained the number-one concern for livestock producers for more than a year, and this looks to be the case in the coming months.

Ukrainian infrastructure damage causes concern

Along with the tragic and significant loss of life since the war in Ukraine began earlier this year, the movement of grains and other commodities has been challenged by damage to critical infrastructure and the closure of seaports.

Ukrainian grain exports in March were a quarter of the volumes reported in February, with only 1.1 million tonnes of corn, just over 300,000 tonnes of wheat and almost 120,000 tonnes of sunflower oil moved to export destinations via rail.

The closure of ports has caused significant backlogs and bottlenecks on rail corridors and has dramatically increased the cost of moving grain out of Ukraine. According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), this conflict has fueled a marked increase in the price of sunflower oil globally.

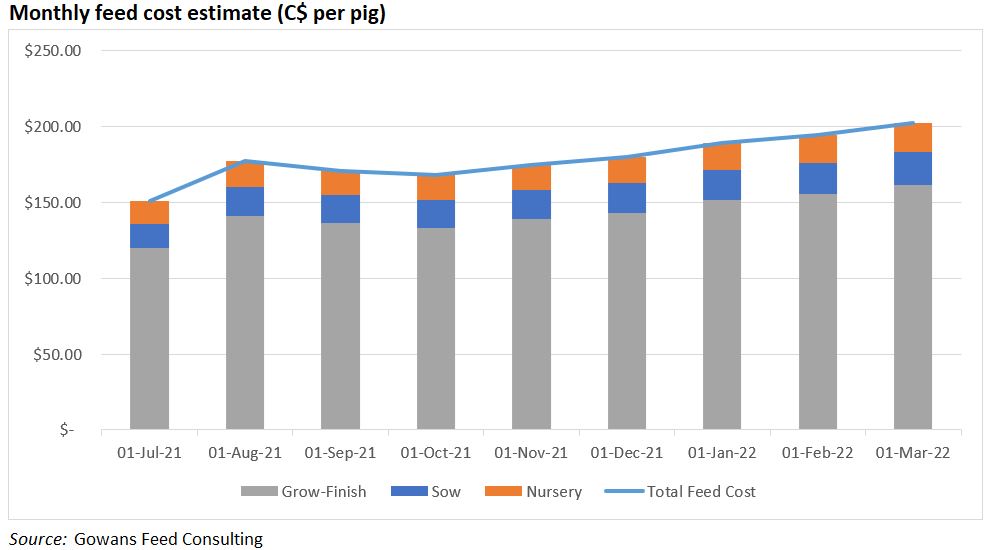

South American drought ravages soybean crop

Dry conditions have devastated crop yields in South America recently. Brazil’s soybean crop is expected to fall below 120,000 metric tonnes for the first time three years. The drought has been felt not only in Brazil, with soybean production projected to be down nine per cent in Argentina and 37 per cent in Paraguay.

Soybean prices, which had pulled back from a high point in January 2021, have risen sharply again to a seven-year high since then, in response to the lack of moisture. With tighter supplies in South America, the higher global prices may stick around until the North American harvest.

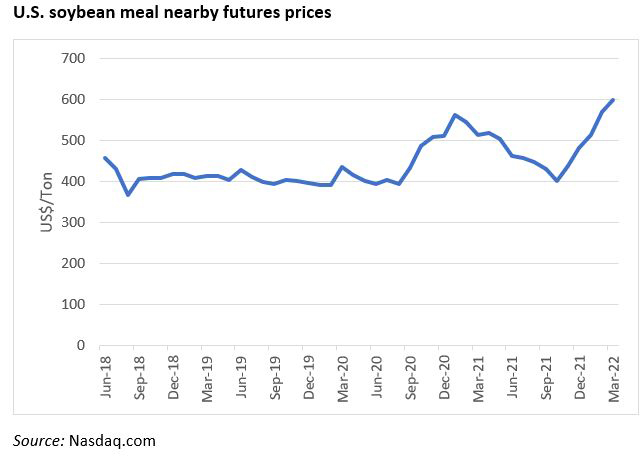

North America could be drier than usual this summer

In the U.S., growing conditions look less-than-favourable this year. The La Niña effect has caused a warmer- and drier-than-usual winter. According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), most of the country will be unseasonably warm between April and June, with some of the drier areas representing grain-producing regions. Drought conditions are expected to persist or develop for most of the western half of the U.S. over the next few months.

Production of hard red winter wheat this year, which makes up nearly 40 per cent of total U.S. wheat production, plunged 44 per cent because of drought in the northern plains. Areas in the Dakotas are still experiencing moderate drought conditions, and a repeat of last year could significantly disrupt U.S. spring wheat supplies.

Data out of Canada also points to some drier-than-normal precipitation levels over a significant portion of the arable prairies this spring. This is troubling, given that the region is coming off a year when feed grain supplies faced a 42 per cent shortfall in some areas and only a six per cent surplus in others. Another dry year could lead to significant feed disruptions.

Feed barley exports continue to grow

Coming off a drought-impacted 2021 harvest, feed grain exports from Canada continued a second year of decline. Crop year-to-date, 1.1 million tonnes of feed grains were exported as of early April. At this rate, Canada would be on target to export 1.7 million tonnes of feed grains by the end of July, down 9.3 per cent from last year.

Nevertheless, feed barley exports continue to increase. Last year, 1.5 million tonnes of barley were exported, and this year, Canada is on track to export 1.6 million tonnes, with almost all the crop pushed through the west coast terminals likely destined for Asia.

In a year when prices are supposed to be high because of feed shortages, the free market continues to dictate where grain is sold – to the highest-paying buyer. In this case, that means foreign markets. This has exacerbated shortages and pushed domestic feed grain prices higher, making hog production less profitable than it might be if the trend favoured selling into the domestic market.

Geopolitical strife always has a role in markets

Some countries have, in light of the global events earlier described, made efforts to ensure grain supplies. Egypt, Algeria and Serbia are a part of a list of countries that have banned the export of grain or food to combat their perceived food security problems.

China is the largest grain buyer in the international market. However, it would appear China is taking a protectionist stance by banning exports of its own fertilizer, in a bid to support its own domestic production. Observing this strategy, it calls into question whether the Canadian grain and livestock industries could work more closely together to benefit producers of all commodities.

The lack of fertilizer supply globally has driven up prices and increased the marginal cost of producing grain. This means that both food and feed grains will become more costly this crop season, even as Canada continues to ship feed grains out of the country, resulting in financial strain for domestic livestock producers.

While hog futures are looking favourable heading into summer, costs continue to push higher, offsetting much of the potential gains.