By Andrew Heck

Livestock disease outbreaks are never good but having the right resources to detect and defend against disease is critically important for the entire pork value chain.

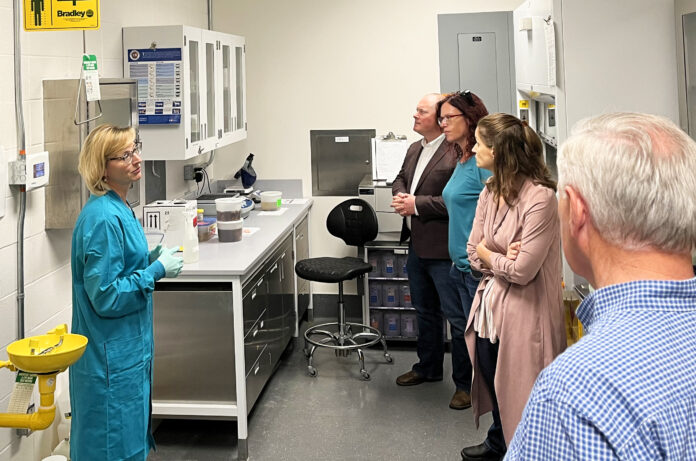

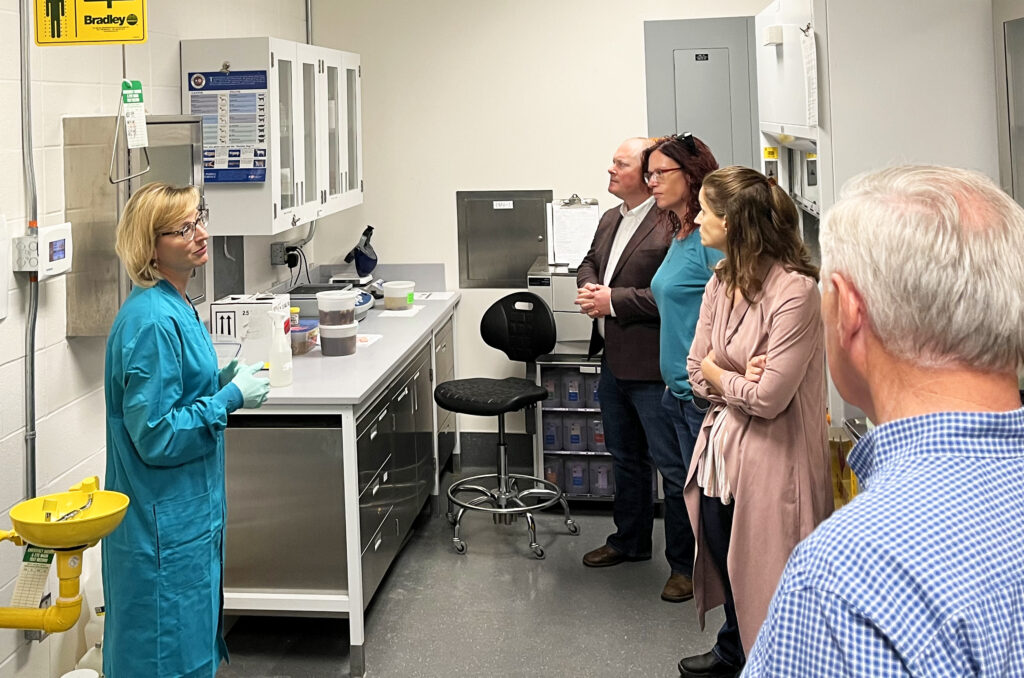

The University of Calgary’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (UCVM) Diagnostic Services Unit (DSU) opened in 2010 and offers fee-for-service testing. In 2020, through the Enhanced Livestock Diagnostics pilot project, the fees became Alberta-supported for livestock submissions, resulting in more affordable costs compared to shipping out-of-province.

Located in northwest Calgary, at the university’s Spy Hill campus, samples are received during regular business hours with after-hours drop-off available around the clock, seven days a week, excluding the Christmas break. Most preliminary results are received within two days, depending on the type of diagnostic test. This shift toward industry diagnostics broadens the lab’s previous focus, which was aimed more toward students and research.

“We can test any species that isn’t human, including wildlife,” said Lindsay Rogers, Program Outreach Coordinator, DSU. “Under the terms of our grant, several species of production animals are covered, including pigs, cattle, poultry, sheep, bison, elk, deer and other species.”

With funding through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership (CAP) and Results Driven Agriculture Research (RDAR) until 2024, use of the DSU has seen a significant uptick since transitioning.

“The DSU acts as a hub for vets, so we don’t have to look for different labs,” said Rienske Mortier, Veterinarian, Prairie Livestock Veterinarians. “It’s very convenient, and the lab staff have a great sense of communication with us.”

For producers, having a direct diagnostics pipeline should be reassuring, as time is of the essence whenever clinical signs of disease are observed in a herd.

“What the DSU offers for producers is a close-to-home, timely outlet for confirming or negating the presence of a pathogen,” said Javier Bahamon, Quality Assurance and Production Manager, Alberta Pork. “One of the most difficult parts of disease investigation is nervously waiting on results, but DSU cuts this time dramatically for detecting diseases.”

Not only as a threat to animal health, livestock disease can have implications for food safety and international trade. As such, disease detection and surveillance are crucial for the industry.

Diseases differ, detection stays the same

Depending on the suspected disease, it may be reportable or notifiable at the provincial or federal level of government. ‘Reportable’ diseases are those that pose significant threats to animal health, public health or food safety, requiring a response to control or eradicate. ‘Notifiable’ diseases are those that are monitored for changes or unusual trends.

Federally reportable diseases affecting pigs include, but are not limited to, African Swine Fever (ASF), Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) and Trichinellosis, while provincially reportable diseases in Alberta would be forms of swine coronavirus, including porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED), delta coronavirus and transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE). Alberta’s 2019 outbreak of PED, pre-dating the transition of the DSU toward industry diagnostics, was confirmed three days following sampling. If in-house PCR testing is established at the DSU, improved turn-around times for cases such as these would be likely.

“We are obligated to pass information on to the provincial or federal government in the case of a reportable or notifiable disease, but the advantage for vets and producers is response time,” said Rogers. “Moreover, anonymous data from investigations makes its way back into educating our students, who will become the next generation of professionals in the industry, so it’s a full-circle process.”

Even when tests return negative results for a suspected pathogen, the information adds to the knowledge of animal health status across the province, which has value for disease prevention.

“We’ve performed thousands of tests at high-traffic pig sites for nearly eight years,” said Bahamon. “The vast majority have come back negative, and with the added capacity of the DSU, testing is easier and more affordable than before.”

Following the completion of a test, the DSU bills the herd vet, and the herd vet then bills the producer. Because the DSU operates with grant funding, Alberta-based vets are offered services at a discounted rate, which may be passed on to their producer clients. The financial incentive alone ensures producers are not stuck with additional on-farm costs, and it lowers the price tag that is often inevitable with herd health monitoring.

“It’s win-win for producers,” said Bahamon. “Your vet helps you, the lab helps the vet, and quicker testing can result in potentially quicker disease response.”

Less guessing, more checking

Symptoms of disease can be confusing, even for vets. Often, they are straightforward enough to be observed with the naked eye or based on changes in productivity, but it is impossible to be sure of disease without testing.

“It’s sometimes possible to accurately guess what’s going on in a barn, but you never know until you test,” said Mortier. “If I think something is viral, and I’m not sure what it is, I can still send it to the DSU and get a better idea. I don’t have to discriminate, which is the nice thing.”

In fact, Mortier has had positive disease cases confirmed by the DSU.

“Breaks of diarrhea in nursery barns with piglets are not totally uncommon, so I wasn’t sure what was going on in one particular instance,” said Mortier. “I sent a bunch of samples to the lab, and within the day, they were able to tell me the issue was Salmonella. I had to immediately inform the barn about the problem and create a plan of action. After that, follow-up testing was done for further analysis and to determine a path forward.”

In livestock, various types of Salmonella infection are provincially reportable in Alberta. When consumed by humans, Salmonella can present a major risk of foodborne illness. Between 2020 and 2022, the Government of Alberta reported nearly 70 cases of Salmonella enteritidis in livestock, but numbers can be deceiving. Is a high number a good thing or a bad thing? Ultimately, any number of disease cases discovered creates an opportunity for positive change.

“It’s better to know than not know,” said Mortier.

Plenty to celebrate, more to gain

Going forward, Alberta Pork hopes for continued support for the DSU, given its value to producers.

“We want to do everything we can to promote the services of the DSU for the benefit of our producers,” said Bahamon. “Producers and vets have a huge opportunity to leverage the potential of the DSU to improve their own operations and protect the industry at large.”

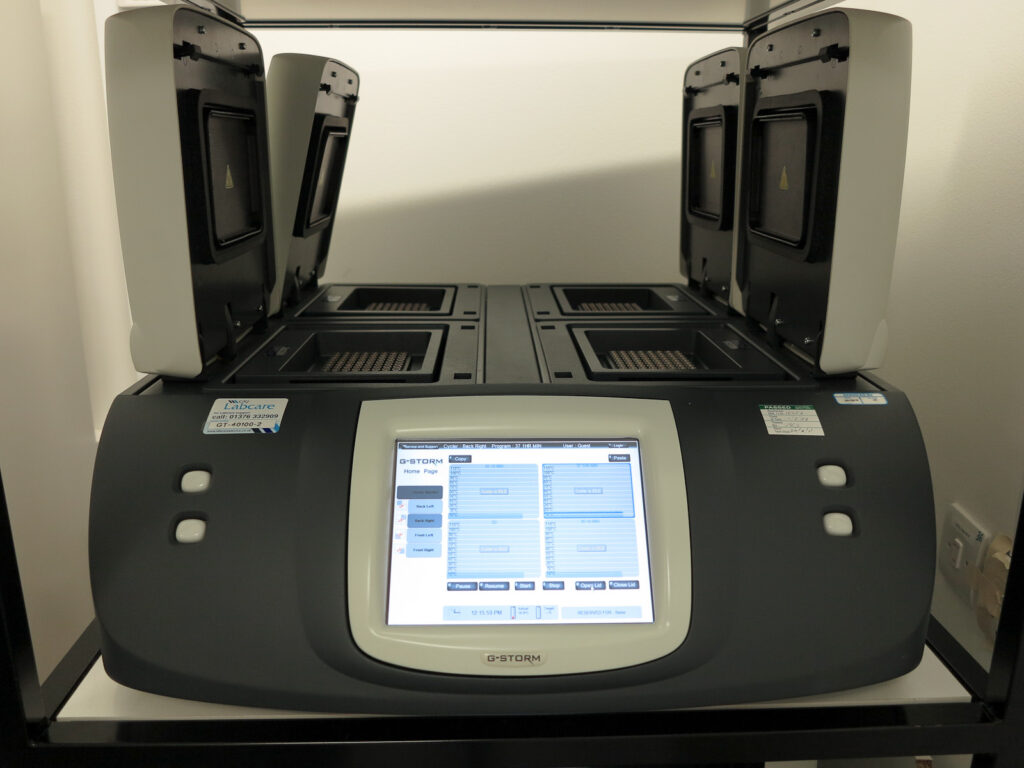

Currently, nearly half of all cases referred to the DSU required polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing as a secondary step to verifying samples; however, this capacity does not exist in-house.

“We do still have to send some samples out for validation,” said Rogers. “Additional capabilities within our lab and team would be required to streamline this process, but it would represent a desired improvement.”

For now, having a state-of-the-art livestock disease lab in Alberta, for Alberta producers, is a major plus when it comes to disease prevention and response. Pork industry partners and end-users, likewise, can have confidence that the value chain’s ability to manage pig health is strong and getting even better.