By Andrew Heck

‘Environmental, social and governance’ (ESG) goals: you may have heard of them, and you may be skeptical that they are a hip but unsubstantial layer within the complexity of big business. On top of that, you may be wondering what they have to do with agriculture at all, or at least raising pigs or selling pork.

Like a cultural tsunami, these corporate priorities have swept up investors, executives and media pundits alike, and they are probably coming to a barn and processing plant near you, soon, if they have not already arrived.

In fact, two presenters at the 2023 Banff Pork Seminar, Mauricio Alanis, Director, Sustainability Strategy & Partnerships, Maple Leaf Foods and Banks Baker, Director, New Product Marketing, Pig Improvement Company (PIC) are riding the crest of that tidal wave but bringing plenty of hope and encouragement along with them, rather than heavy-handed morality or guilt-inducing tactics of those who sometimes like to pick on the livestock sector.

Alanis and Baker were recruited to speak about their companies’ sustainability commitments, what they mean and, most importantly, how they are measured. And they did so with a great deal of fluency and convincing, providing some helpful insight into where sector leadership is headed in the very near future.

Maple Leaf considers all aspects of production

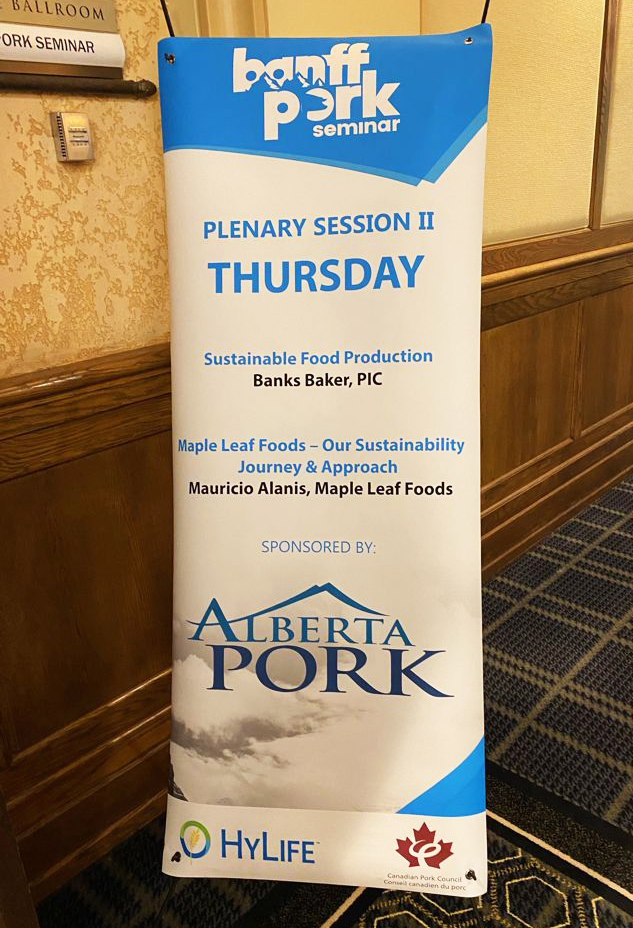

In 2019, Maple Leaf Foods declared itself the ‘world’s first carbon-neutral food company,’ based on its systematic approach to avoiding, reducing and replacing emissions of carbon dioxide.

According to Mauricio Alanis, throughout Maple Leaf’s operations – from farms to packing plants and beyond – the company uses instruments to measure carbon dioxide releases, where possible, such as from manure lagoons. These readings are validated by an unbiased party, for accuracy. Whatever carbon is unable to be mitigated by making process optimizations is offset by the purchase of carbon credits.

“Offsets are not the solution; they are part of the solution,” said Alanis. “They keep us honest on our sustainability journey.”

The idea behind purchasing offsets is to contribute to investments in projects that work toward addressing carbon intensity in all kinds of areas inside and outside of agriculture. Offsets are verified by third-party registries that endorse projects based on their ability to make a difference in the bigger picture. Projects include renewable energy development, anerobic digestion of manure for electrical generation, regenerative crop production and carbon sequestration.

Maple Leaf’s ‘carbon inventory’ spans everything from greenhouse gases (GHGs) resulting from barn heating and other production inputs, to emissions from feed crop production and end-use considerations like transportation and packaging materials for its food products.

But, for Maple Leaf, sustainability takes into consideration more than just emissions. Alanis believes the food industry today faces a burning platform in terms of emissions, antibiotic use and food waste. The intersection of what the world needs and who you are creates purpose, and that is the driving force behind the company’s sustainability initiatives.

“It’s not just the bacon you scraped off you breakfast plate. It’s everything that preceded it,” said Alanis. “We can do good by food, and we can promote our industry’s positive effect on society.”

Maple Leaf is currently the largest producer in North America when it comes to pork raised without antibiotics (RWA), representing a 99 per cent reduction in use across company-owned hog operations since 2014. Maple Leaf previously committed to ending gestation crate use by 2024 and exceeded that target by meeting the goal in 2021. Additionally, the company’s own farms also recycle 100 per cent of hog manure, by using it on crops.

The business case for sustainability is also not lost on Maple Leaf. Following consumer trends and making marketing claims is an important part of the follow-through on their initiatives, which translates into company profits.

Product claims on packaging highlight the company’s values in “delivering nutrition, affordable and sustainable food choices that don’t compromise on taste,” which appeal to some consumers’ appetites for a ‘better’ product than comparable goods that are, perhaps, unable to make the same claims regarding carbon neutrality, animal welfare and meat quality – even if those claims ultimately rely on perception and preference.

For an integrated producer-packer with retail-branded products, like Maple Leaf, it all adds up to consistently favourable meat margins, even though the company’s plant-based portfolio has yet to make much profit, if any. While many producers may not always consider the value added by processing to be returned to them, at the independent farm level, it stands to reason that Canadian companies like Maple Leaf need to stay on the cutting edge to compete with even larger players around the world, including next door in the U.S. Any loss of global pork market share by the likes of a Maple Leaf or another major packer in Canada ultimately spells worse outcomes for Canadian producers.

PIC approaches carbon reduction differently

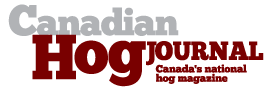

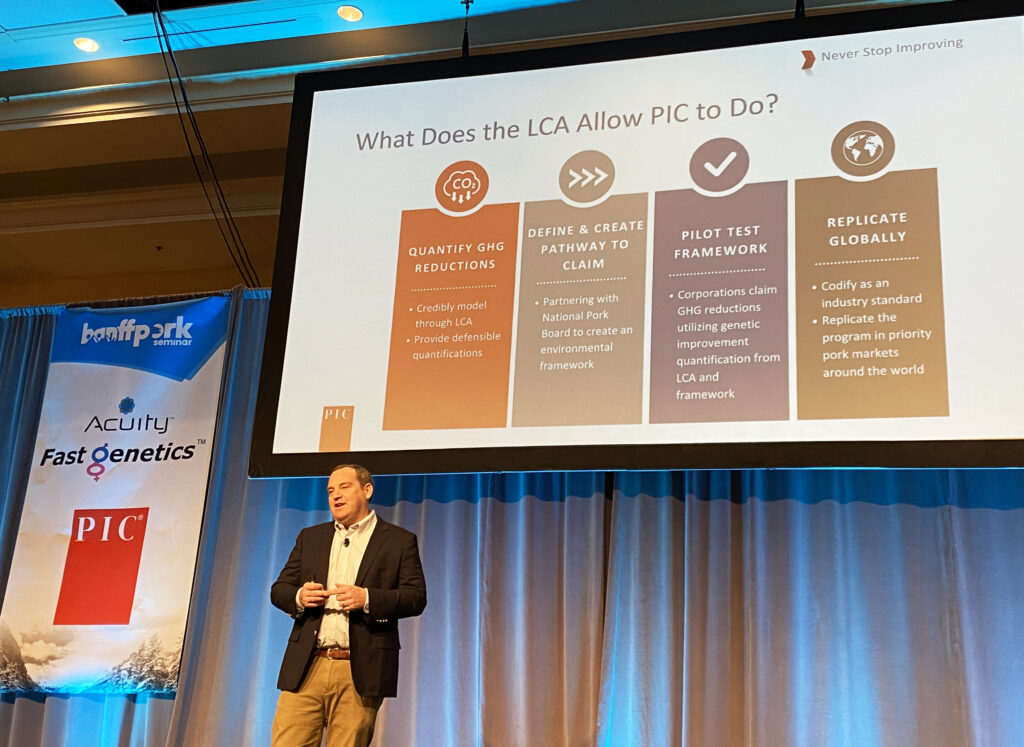

While Maple Leaf Foods is focused on addressing sustainability across its supply chain, PIC is looking through a wider lens and working to make pigs that naturally pollute less, through gene editing. PIC is working with industry partners to develop a genetics framework, which, once developed, will be available to all swine genetics companies.

It is a decidedly contemporary direction for the genetics sector. Not only does the framework have the potential to reduce the carbon intensity of pig production, but performance, too, could see gains and cost savings with fewer inputs.

“Agriculture is being asked to do a lot,” said Baker. “And we’re being asked to do this in the face of a food affordability challenge.”

While lower-carbon pigs will not bring grocery shoppers’ bills down, they do conform to a trend that is being seen across the business landscape. Companies spanning the industrial spectrum are aligning with the Paris Climate Accords: science-based targets set out by the United Nations (UN), covered under a treaty signed by all 194 UN members, including Canada, and representing more than one-third of global market capitalization today.

“I’ve heard from some people they don’t believe in climate change or that they don’t believe it’s caused by humans,” said Baker. “I’m here to say, it doesn’t matter. Our customers are asking for these things, and our governments are compelling them.”

Baker points to the U.S. Government’s net-zero commitment by 2050.

“When you look at this from a logical deduction standpoint, what’s coming next? Is it something like a carbon tax?” said Baker. “This is on our doorstep. This is here.”

While planet-minded pigs could certainly boost the hog industry’s image, improved genetics also have obvious profitability benefits for the producers who raise them. As genetics companies and other suppliers make these kinds of climate commitments, Baker feels it is important to reward producers for assisting in the process, by providing financial incentives.

There are even opportunities to build bridges with critics. Animal activists may support animal welfare improvements through gene editing, which also contributes to company sustainability. When it comes to those who question the safety, healthiness or taste of eating pork from gene-edited pigs, and whether that could deter consumers, Baker is not worried.

“PIC has been in this business for 60 years, and we plan to be in it for another 60,” he said. “We’re not trying to interrupt choices or jeopardize trade.”

Whether sustainability comes in the form of enhancements to genetics, on-farm production, processing or end-use efficiencies, the challenge will remain for the entire industry to equitably spread the benefits across the value chain.

Sustainability can improve image and bottom line

All told, the discussions around sustainability in agriculture must continue to balance saving the planet and saving profits – but that is not necessarily a bad thing.

Whereas navel-gazing and self-consciousness are a real risk with these discussions, producers, packers and everyone with a stake in food production (which includes anyone who eats food) should consider that the weight of world hunger – sad as it to acknowledge – must ethically outweigh sentimentality around environmental concerns, even if those purported concerns are said to exacerbate food insecurity, which is a shaky argument, at best.

Sustainability matters, but only if food is making it onto the world’s plates. This does not, however, mean that pie-in-the-sky idealistic thinking can be ignored, since, without it, progress is seldom realized.

Working to curtail the carbon intensity of the hog industry, while also being mindful of other consumer demands that tend to overlap this issue, is still a relatively unexplored frontier. ‘First mover advantage’ may not have disappeared yet for agri-businesses, when it comes to novel concepts regarding sustainability, but there will come a time when that ship has sailed, and the scrutiny will shift toward those who have failed to adapt as quickly. Today’s values-based consumer or foreign buyer will have the option of simply looking elsewhere for their purchases – perhaps a commodity other than pork or a country other than Canada, altogether.