By Treena Hein

The latest on-farm best practices relating to all phases of production were shared as part of several presentations during three management-focused breakout sessions during the 2023 Banff Pork Seminar, including the impact of mortality and efficient feeding.

Lee Schultz of Iowa State University and Kurt Stoess of HyLife showcased their work and how it can save money for producers.

Putting a price on mortality

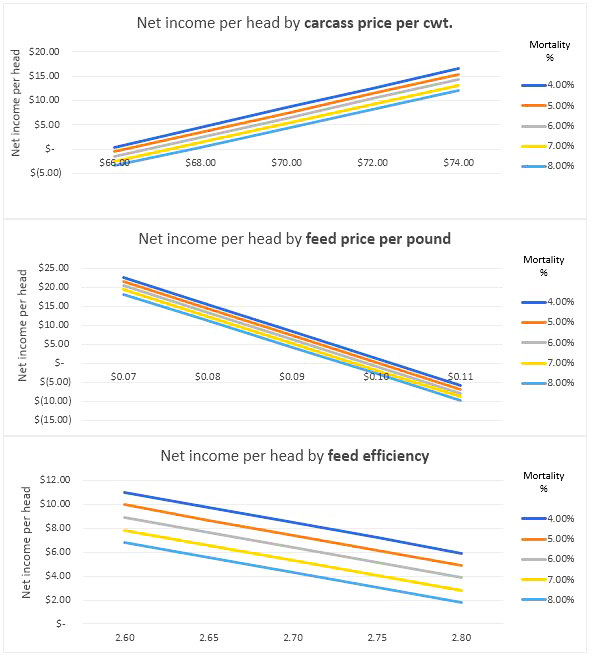

With colleagues from his university and others, Lee Schulz has been working on a spreadsheet-based decision tool to help producers examine the costs of reducing mortality on their operations by a certain level. It is important, he said, to determine whether the costs are worthwhile in terms of the profit benefits of the lowered mortality.

That is, there is an optimum total farm profitability level of mortality that can be determined for any given operation. Producers should note, however, that this level can also change over time. Schulz stressed that economists think differently about the optimal level of mortality compared to producers in general.

“It’s where marginal revenue, the last dollar I get, is equal to marginal cost, or the last dollar that I spend,” said Schulz. “It sounds really simple, but it isn’t. It’s a very different task to calculate it.”

Schulz further explained that the value of a dead pig should not just be measured through the money that has been invested in that animal up until the time of its premature death, but must also include the lost revenue that would have been received had the pig provided its maximum profit, similar to what its fully grown peers brought in, at the point of marketing. The cut-out value and not just live weight at marketing should be the focus.

He also suggested defining the value of, for example, what a percentage point drop in mortality would do related to the return realized for the costs involved.

“When you think about making a change on your operation, you usually know the cost because someone’s quoted you the cost of an animal health intervention, a nutritional intervention,” said Schulz. “But you need to know the value of it in order to decide whether you should incur that cost.”

He then illustrated with the decision tool an example of comparing the value of going from six to five per cent mortality. The spreadsheet is simple and easy-to-use while factoring all the information needed for good analysis. Producers tailor the information to their farm and also input current market characteristics. Schulz explained that a large part of the calculation is the average weight of pigs at death.

“The later they die, the less cost savings producers have,” said Schulz.

He added that there might be some differences in the calculations of wean-to-finish feed efficiency that come with changes that producers employ, to try and reduce premature death, but everything else in the calculation needs to stay the same – feed costs, for example – in order “to tease out the true cost of that one per cent of mortality.” He also added that the overall cost of reducing mortality can vary depending on the cause.

While it may not be completely exact, Schulz insisted this tool is a valuable starting point for producers to weigh the projected benefits of mortality-reducing strategies against the anticipated costs.

Feed-related choices can be significant

The critical importance of ongoing in-depth conversations with your nutritionist is what Kurt Stoess stressed. He urged producers to discuss many aspects of their swine diets with their nutritionists on a regular basis if they want to see farm performance improve.

“Nutritionists are one of the biggest influences on your feed costs, which covers two-thirds of your costs,” said Stoess. “The other thing I want you to remember is that your farm is unique, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution to your problems.”

Stoess advised that nutritionists must, first of all, know the pig you are feeding in terms of any change in genetics, or new information that may become available from your genetics firm, along with gender, health status, target end weight and any other updated packer specifications.

Referring to the feed itself, Stoess touched on energy, amino acid ratios, ingredient availability, feed additives, mash versus pellets and the reformulation schedule.

Energy is divided up into maintenance, growth or challenges, he explained, but that growth is a complex aspect that needs close attention from you and your nutritionist.

“At the beginning of your finisher batch versus late in your finisher batch, for example, you may want that growth to be doing different things, and a lot of this is dependent on genetics,” said Stoess. “In the beginning, you’re going to get more lean deposition versus fat deposition, so maybe you want your nutritionist to feed higher energy there if you get bonuses for loin eye size and things like that – maybe there is payoff there.

“Vice versa, maybe you just want to keep your energy level steady throughout your whole feeding stage and let things play out, or maybe you drop your energy level at the end. Maybe your back fat needs to rise [at the end] if your genetics are very lean, and you will get penalties for having it too low. There is no one right answer, but you need to have that conversation with your nutritionist.”

With amino acid ratios, the key, in Stoess’ view, is to continue learning and keep abreast of new findings. Similarly, Stoess encouraged regular discussion about all the latest feed additive developments. One newer finding he pointed out relates to feeding ionophores, where there are bigger benefits being seen with higher-fibre diets.

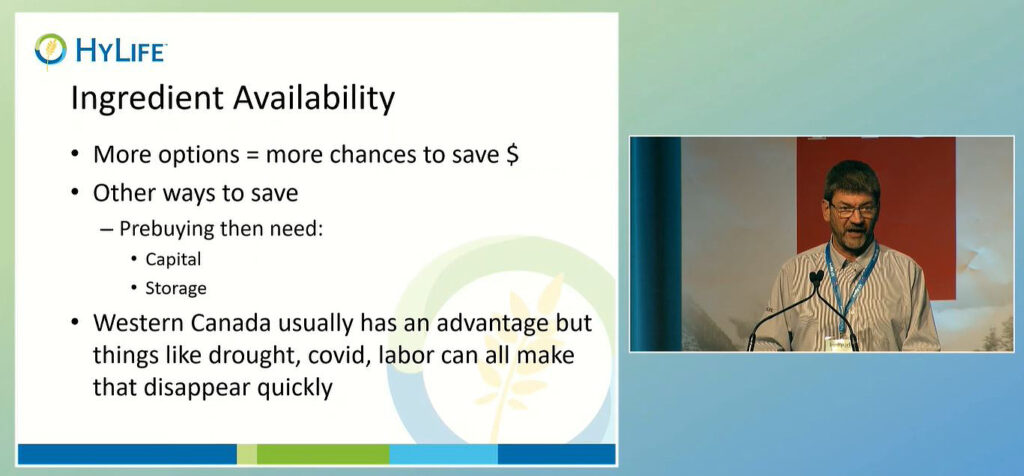

On the ingredients front, he noted that western Canada usually has good advantages for availability, but things like drought, labour and other factors can get in the way quickly. Comparing mash to pellets, he said that, while pellets cost more but have more benefits, particle size is important. Pelleting wheat and barley has more benefits than pelleting corn.

To maximize the value of reformulation, Stoess strongly recommended that producers and their nutritionists have a prescribed plan as to how often diets are being assessed and what factors trigger reformulation.

“How does that work?” asked Stoess. “As your nutritionist is running different scenarios and trying to least-cost your diets, you both have to also remember ingredient availability, so you need to have constant communication.”

Producers and nutritionists also need to decide how to implement stage feeding plans and perhaps increase the number of stages. With only three, he believes producers are leaving money on the table and instructs that five to seven is best. To determine where one stage ends and the next begins, “I like to go with tonnage [rather than weight],” said Stoess, “as it’s nice and simple to control.”

Overall, he also thinks producers should work with nutritionists to focus on gut health through vaccinations, investing in veterinary advice, and using ionophores and feed additives such as essential oils.

“If you focus on improving your gut health from day one, when those little health challenges happen, they will not affect your bottom line nearly as much,” said Stoess.