By Lexie Reed

Editor’s note: Lexie Reed is a food animal veterinarian based in Lethbridge, Alberta. She can be contacted at lexiereedvm@gmail.com.

Swine health is an important and popular topic every year at the Banff Pork Seminar, and 2023 was no different. This year, breakout sessions included information about Streptococcus suis (Strep suis) and Escherichia coli (E. coli) in the nursery, along with a veterinary practitioner’s perspective on circovirus in the present and future.

Brooke Smith of Cargill Animal Health and Nutrition, and Ryan Tenbergen of Demeter Veterinary Services, led these respective sessions, focusing on what should matter to producers.

Strep suis and E. coli in the nursery

Smith led session attendees through novel health management tools for the purpose of improved nutrition – an area of innovation that combines her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine with her PhD in swine nutrition.

“Increased virulence of common pathogens and increased resistance to antimicrobials creates an opportunity for additional health management strategies. If we know the mechanism by which a pathogen causes disease, that can give us a clue as to what nutritional intervention is best able to target the pathogen,” said Smith. “When it comes to nutritional interventions, I have two approaches I can take: directly interfering with the pathogen’s ability to colonize the pig, or improving the immune system’s response to the presence of the pathogen.”

These approaches can be deployed on common nursery pathogens like Strep suis and E. coli. Strep suis infection in nursery pigs is often a function of combined factors: primarily, concurrent viral disease, ventilation and temperature; genetic predisposition; high stocking density; and dietary changes.

“All commercial pigs are a carrier of at least one serotype of Strep suis,” said Smith. “When we move pigs into a nursery, some pigs have never seen the serotype that the other litters have. We combine all of those external stressors to a naïve population that is faced with a serotype they have never seen before, and it creates an opportunity for clinical disease to occur. Tonsilar epithelium is the predominant site of colonization in Strep suis serotypes found in North America.”

Nutritional strategies to limit colonization include using amino acids to manipulate pig growth rate and to increase nutritional support towards the immune system. Smith and her team at Cargill are exploring how reducing amino acid concentrations in the diet early in the nursery phase could help, by diverting these amino acids away from rapid growth, which puts metabolic stress on the pigs, towards the immune response. And then there are functional proteins, like plasma, that directly contribute to improved immunity.

“Because that infection is not localized to the gastrointestinal tract, and Strep suis spreads systemically after it colonizes the tonsils, I need to start thinking about nutritional strategies that are absorbed, metabolized or circulated, rather than just having an effect at the site of the intestine,” said Smith. “Not only is plasma a highly digestible and palatable source of protein, it also contains compounds like immunoglobulins that bind pathogens in the gastrointestinal tract, which is work that the immune system would have to do otherwise.”

Phenolic compounds – the natural defense molecules in plants – have direct antimicrobial properties and can be added to the nursery diet.

Another ubiquitous nursery pathogen that Smith and her team are working on addressing is E. coli. The site of colonization of E. coli in the pig is the small intestine, where it binds specific receptors on enterocytes – the cells lining the interior surface of the small intestine. The expression of these receptors can be up- or down-regulated by age, genetics and prior or concurrent gastrointestinal disease like Rotavirus and coccidia. The severity of E. coli infection is increased by cool and damp environments, poor sanitation, the transition to a plant-based diet, reduced feed intake and high stocking density.

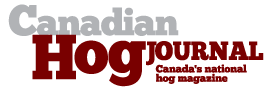

“For us as nutritionists, this means that we have the potential to use ingredients that will have prolonged contact with E. coli in the gut. Or I can use the diet to create an unfavourable environment for E. coli to grow,” said Smith. “One strategy for a base diet is to increase dietary fibre. This increases the turnover of the cells lining the intestine and stimulates mucous production, which blocks E. coli from binding onto the receptor site of the cell.”

Mucilages are additives that act in the same way when they reach the small intestine. Another strategy is the use of essential oils, which can physically alter the cell membrane of bacteria and disrupt the communication between E. coli, making them less able to colonize the intestine.

While nutritional strategies can help, they alone cannot manage disease in nursery pigs.

“A number of nutritional strategies and ingredients are available, but understanding what type of pathogen is driving clinical signs, and how, is key,” said Smith. “External factors impacting exposure to, and dynamics, of disease need to be addressed. This includes managing husbandry, environment, genetics, concurrent disease and population dynamics.”

Circovirus: a practitioner’s perspective

Ryan Tenbergen led his session with an important takeaway message: “Do not forget about circovirus!”

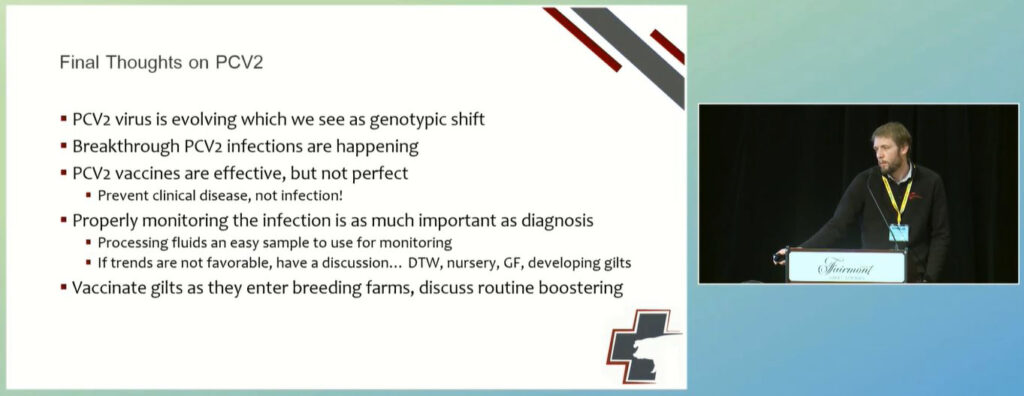

Circovirus vaccines, which have been available commercially in North America since the early-2000s, are largely successful at controlling Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2). However, there have been reports of PCV2 clinical disease in vaccinated herds in recent years. PCV2 causes a wide range of clinical presentations. One of the hallmarks of the disease is this varied clinical presentation and severe immunosuppression.

“In order to stay ahead of circovirus-associated diseases and avoid the potential of significant losses associated with clinical disease, we need to rethink circovirus monitoring and vaccination strategies against it,” said Tenbergen. “It’s multi-factorial. You have infectious and non-infectious causes, and then circovirus is there to cause clinical disease. Generally, alone, it’s hard to produce disease.”

PCV2 monitoring can be done with PCR testing on processing fluids, tissue or blood. A positive PCR test would indicate replicating and circulating virus in the body. Some studies have found this to be associated with negative growth performance in growing pigs, suggesting that a subclinical PCV2 infection is occurring; however, it is important to note that PCV2 is widespread in swine populations. PCV2 is in barns and circulating in pigs, but just because we find it in pigs does not mean it is causing disease.

Tenbergen stressed that when interpreting PCV2 PCR results, it is important to look at the degree of positivity and the cycle threshold (CT) value. The degree of positivity is the proportion of positive samples in a total sample submission. The CT value is the number of times that the PCR process had to be run in order to detect the virus. The more virus present, the lower the CT value will be. When there is a high percentage of positive samples and CT values are low, the more likely PCV2 is circulating at high levels in the herd.

Referring to a summary of Demeter’s PCV2 lab results, Tenbergen said, “What’s interesting is that, in 2021, there was an increase in strong positive results. Generally, as pigs get older, we see more positive results. We are more likely to find it in the finisher than the nursery.”

Tenbergen shared some case studies of farms in Ontario that presented with high mortality after weaning. On these farms, pigs would fall back after weaning. One week after weaning, pigs began to lose condition, and in two to three weeks post-weaning, mortality would spike anywhere from 10 to 30 per cent. In these herds, a co-infection with porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome (PRRS) virus was also present, and in some of the herds, so were porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome (PDNS), an inflammation and dying off of the underlying skin structures that appears as dark patches of skin on the hind limbs and underside of the pig.

“If you see PDNS, it is worth investigating if PCV2 is present in these pigs,” Tenbergen advised.

In these herds, antimicrobial treatment had little effect on reducing mortality in the growing pigs. However, mass vaccination of the sow herds and an addition of a PCV2 vaccine in piglets at processing (two to four days after birth) in the short-term successfully reduced disease and mortality in the growing pig herds.

So why do PCV2 infections occur in herds that are vaccinated? Tenbergen explained that this happens when sow immunity is not uniform in the herd. When pigs are born infected or become infected early in life with PCV2, vaccination is ineffective, and the disease spreads among the growing herd. To achieve stability, gilts and sows must have immunity to PCV2 so that they do not shed it to their piglets. Vaccinating the female breeding herd achieves this goal of uniform immunity.

“I think monitoring the herd status and determining the stability of the herd should be a priority,” said Tenbergen. “With a higher PCV2 natural challenge, a one-dose program isn’t enough to carry them through their entire lifetime.”

Tenbergen explained that herds with high replacement rates in gilts are at greater risk of PCV2 instability in the sows. Incoming gilts could be susceptible to the strain of PCV2 in the barn or could bring with them a strain not present in the herd. PCV2 has the ability to re-combine, and co-infection of more than one PCV2 has been reported in Canadian diagnostic lab data.

Tenbergen noted that it is common for replacement gilts to receive only one dose of circovirus vaccine at weaning. In addition to PVC2, Tenbergen implored producers to consider the emerging Porcine Circovirus Type 3 (PCV3). PCV3 was first recognized as causing clinical disease in 2016. Though both PCV2 and PCV3 fall under the same broad virus family, Circoviridae, they share less than half of their genetic similarities. Like PCV2, PCV3 is thought to be endemic in herds and likely has been circulating in the swine population for years. PCV3 has also been reported to cause post-weaning multisystemic wasting, reproductive failure and PDNS. Looking at Demeter lab data, Tenbergen reported an increasing trend of PCV3 positives from 2020 to 2022. He has found three clinical cases of PCV3 in Ontario to date.

“Looking at PCV3 results, there are more positive results than negative, and the strong positive results are increasing each year,” said Tenbergen

Tenbergen reminded session participants that PCV vaccines are effective, but not perfect, and that the disease continues to evolve. His final suggestion was to consider implementing a PCV2 monitoring program in the herd and consider routine PCV2 boosters in the breeding herd. He recommended that PCV3 positive test results be interpreted in light of the pathological and clinical findings in the herd.