By Swine Innovation Porc

Editor’s note: This article is a project summary prepared for Swine Innovation Porc, as part of a series of articles covering SIP’s work. For more information, contact ‘info@swineinnovationporc.ca.’

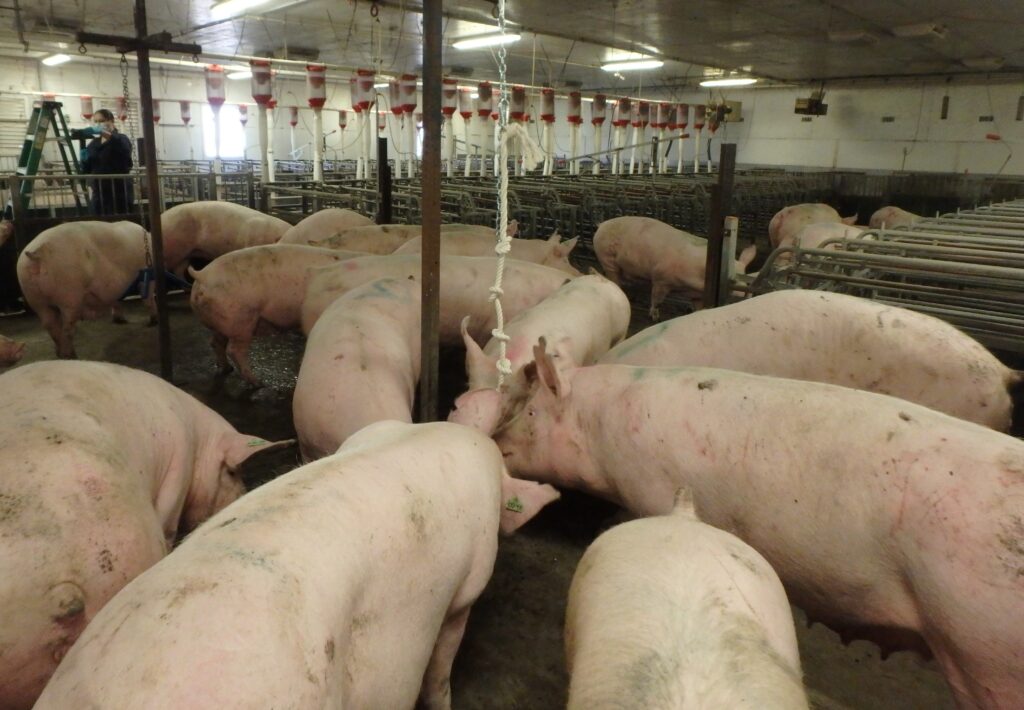

As group sow housing becomes more prevalent in Canadian pig production, understandings its unique dynamics is important. In such systems, proper management is key to minimizing stress for sows, thereby boosting sow reproductive performance and piglet development. Given the stakes for producers, scientists are working hard to find the best approach.

As part of Swine Innovation Porc’s (SIP) Cluster 3 research activities, Jennifer Brown at the University of Saskatchewan explored the pros and cons of different group management systems, focused on dynamic versus static grouping and compared early and late mixing of sows. The University of Saskatchewan’s Yolande Seddon, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Nicolas Devillers and the Canadian Centre for Swine Improvement’s (CCSI) Brian Sullivan also contributed to this work.

With the dynamic mixing approach, multiple breeding groups are housed together in each pen. As small groups of sows are moved out to be farrowed, new groups of recently mated sows join the pen. In static groups, each pen houses only one breeding group of sows. The animals are only mixed at the start of gestation, and no sows can be brought in for replacement if a sow is removed. The choice to implement dynamic or static housing can have big impacts for barn design.

Mixing and mingling

To assess options for group management of sows, the researchers used a variety of mixing times and grouping strategies in the barn. They also followed two of the groups to farrowing and examined the piglets to gauge the impact of pre-natal stress. To assess the piglets, the researchers looked at vitality scores, stress levels, behaviour at tail docking, growth rate and length of time for piglets to approach the udder.

Dynamic mixing is a popular choice for producers, allowing use of new technology and providing individual feeding for sows. But researchers are concerned that there is potential for more conflict, aggression and stress as groups of sows move in and out of the pen. When it comes to sows, there is ‘mixing aggression’ and ‘ongoing aggression.’ Researchers were concerned that ongoing aggression in dynamic groups would be a problem. What they found was that mixing aggression, which happens only once at the beginning of gestation, was reduced in dynamic groups because there were fewer new group members. At the same time, they found that ongoing aggression resulted in more lesions in dynamic groups throughout gestation, but it was not enough to impact their production. This suggests that mixing aggression is more important than ongoing aggression in terms of the impact on reproduction.

Late mixing, after 28 days of gestation, is also largely favoured over early mixing, but this may not be sustainable in the long term for the industry, given incoming regulatory changes to sow spacing during gestation in Canada and the U.S. As a result, researchers are examining early mixing more closely as a viable option.

Interestingly, this study found less aggression in dynamic systems over static ones, in which both were mixed early. In dynamic systems, aggression levels were low when each small group was added, compared to one large mixing event for the static housed sows, which occurred in early pregnancy. The production results were also surprising: dynamic sows had higher farrowing rates than static sows, and even over a control group of late mixed sows.

The research suggests there is not a clear winner between static and dynamic mixing; both systems are popular and will continue to be so. They require very different approaches, so producers must be more aware of those differences to fine-tune management strategies.

Climbing the social ladder

Another important factor influencing a sow’s reproductive performance during this study was social status within the pen. Researchers determined each sow’s rank within the group as dominant, intermediate or subordinate based on a feed competition test. A sow’s rank played a large role in setting their stress level, which, in turn, affected piglet behavior and physiology. The exact connection is not yet clear, but scientists hope to learn more as they review the data.

As part of the project, the researchers also examined sow mortality. Using a survey and follow-up visits that covered 104 herds, they found higher mortality in herds with 3,000 or more sows, compared to smaller herds, and higher mortality in group gestation versus stalls. Scientists were especially concerned that the majority of deaths in group gestation involved younger sows. Apart from the animal welfare implications, early culling represents financial loss. Most producers can attest that sows with fewer than three parities don’t even cover their replacement cost.

These mortality findings are critical for the industry going forward. The increase in lameness should spawn a greater focus on all aspects of gilt development, and genetics companies could prioritize conformation (functional legs and feet) and a calmer temperament that is less prone to aggression. Greater robustness traits would be beneficial as well, making sows more durable in group systems as they navigate concrete floors and interact with their pen mates.

Addressing the mortality issue will take a combined effort from researchers and producers. Appropriate next steps for producers would include increased worker training and ensuring consistency in the use of mortality-related terminology – what constitutes ‘culled,’ ‘euthanized’ and ‘died on farm.’

As group sow housing continues to be more widely implemented across the industry, the more producers can learn about managing group gestation and limiting sow mortality, the better equipped they’ll be to face the future.