By Andrew Heck

Western Canada’s wild pigs run amok

Potential for disease transmission, environmental destruction, physical threats to livestock and other headaches that come with invasive species are what landowners can expect as Canada’s wild pig presence continues to grow relatively unchecked. Because they are intelligent, hardy creatures, eradication has proven elusive.

Ryan Brook delivered the final plenary session presentation at the 2020 Banff Pork Seminar. His team at the University of Saskatchewan has been studying wild pigs for nearly a decade, and population trends suggest that there will be no shortage of further work to do in this area.

“More than 700 delegates who came here to talk about managing pigs inside the fence,” said Brook. “I’m the only one who came here to talk pigs outside the fence.”

“Wild boars” were originally brought to Canada in the 1980s. The current wild pig population is composed of individuals that have escaped captivity, either escaping through poor fencing or being deliberately released.

Efforts to control the wild pig problem in Canada, at present, are sparse, due to a perceived sense of security. We do not have African Swine Fever (ASF), as in Europe, but we do have other swine diseases that could just as easily move from farm-to-farm due to contact with these animals.

In terms of what could stem the tide, Brook suggests more leadership is needed, along with aggressive but calculated culls. There are a couple of reliable techniques available to do this, including use of what he calls a “Judas pig” to lure hunters to an entire group of pigs, also known as a “sounder.” Hunting the animals one by one has proven counter-productive, but trapping and eliminating an entire sounder seems to work. The issue is keeping pace with the growth of the problem, which is not yet happening.

“No one of these points alone will solve the wild pig problem,” says Brook. “It will take a comprehensive plan.”

As for the cost?

“Not sure,” he answered. “Bloody expensive. Hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of dollars. One thing is sure: every year you wait, it gets more expensive.”

Nutrition research focuses on grow-finish and post-wean pigs

Breakout sessions on nutrition were hosted by Mike Tokach and Annie Lerner from Kansas State University, along with Francesc Molist from Schothorst Feed Research of the Netherlands.

Tokach and Lerner delivered the presentation, “Feeding the Grow-Finish Pig and Managing Their Increasing Carcass Weights.”

Their research suggests a historical trend toward market hog weight continuing to increase by more than half a kilogram every year. Genetic improvement allows these heavier weights to be achieved economically; however, long-term increases in market weight require adjustments to production facilities, nutrition programs, transportation and processing facilities.

The maintenance requirements of pigs are proportional to their body weight. Thus, heavy-weight pigs have higher maintenance requirements and must continue to eat increasing amounts of feed to dilute their maintenance needs and provide adequate intake to maintain growth rates.

Heavy-weight pigs have increased capacity to adjust feed intake to different dietary energy densities to meet their energy requirements. Their increased gut capacity allows heavy pigs to digest and use energy from fibrous feedstuffs more efficiently through hindgut fermentation. Thus, producers may have the opportunity to lower feed cost by using fibrous feed ingredients. The potential negative effects of these ingredients on carcass dressing percentage must be considered in their economic evaluation.

Molist delivered the presentation, “Feeding Programs and Nutritional Strategies for Post-Weaning Piglets in the Absence of In-Feed Antibiotics.”

In order to remove in-feed antibiotics in post-weaning diets, it is essential to have a holistic approach and understand the roles of nutrients like fibre, crude protein and fat in promoting intestinal health. The nutritional strategy should be based on formulating low-nutrient post-weaning diets to promote feed intake of the piglets while simultaneously avoiding having an excess of non-digested substrate that can be used for the bacteria to proliferate.

Use of fibre should be concentrated on accelerating the development of the gastrointestinal tract. It is also important to formulate low crude protein diets and use ingredients with high amino acid digestibility. When formulating post-weaning diets, reduce the buffer capacity of the diet to optimize stomach function.

Although, there is still a need for further research on the effect and function of fat and fatty acids in promoting intestinal health, it is advisable to use medium chain fatty acids and optimize the diet, taking into account the proportion of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids.

Sow management starts with gilts

Breakout sessions on sow management were hosted by Dan Bussieres from Groupe Ceres of Quebec, along with Bob Thompson from PIC U.S.A. of Kentucky.

Thompson delivered the presentation, “Factors Involved in Sow Mortality.”

Sow mortality is a multi-factorial problem that increased as our pork industry grew and expanded in the 20th century. A review of 3.6 million parity records between 1996 and 1998 has shown monthly mortality rates were approximately 7.6 per cent in January 1996, reaching a high of 14.5 per cent during the summer of 1998. With focus from researchers, veterinarians, producers and breeding stock companies, it improved to where systems were below 10 per cent annualized with many in the four to six per cent range in the early 21st century. Then, as the industry started to expand again, mortality increased until most systems were back to the low- to mid-teens.

Proper gilt development and acclimatization are essential to build a sound herd. How you receive replacements will drive what efforts are needed to be successful at retaining younger parities and reducing overall sow mortality. Many producers in the U.S. have internal multiplication where herd replacements are raised on-site. With increasing sow productivity and higher replacement rates, it has stressed their systems to have enough good quality select weight gilts. If there are any disease outbreaks, this creates an even larger deficiency.

Reducing sow mortality is up to everyone involved in the pork industry. In Denmark, the industry has set goals to bring about country-wide efforts in this area, for the sake of accountability. If the same does not happen in North America, customer perceptions will eventually force us to act. Why not be proactive?

Bussieres delivered the presentation, “Key Aspects for Capturing Reproductive and Sow Lifetime Performance.”

We often view the success of a sow farm by looking at the number of pigs weaned per sow per year performance, which indeed is important when we look at production efficiency. On the other hand, economically, this number may not be the most important.

Gilts are the foundation of the herd, and a good start with your gilts in their first cycle is key in order to optimize herd lifetime performance. Gilts with higher litter size in their first parity will have a higher retention rate. We should expect our gilts to have the best farrowing rate of the herd and have 14 to 15 total born in their first litter. Also, we should aim for a retention rate of 75 per cent or more up to third parity and achieve between 55 to 60 pigs weaned per lifetime.

Optimizing sow and lifetime productivity starts with a good gilt program. Management and nutrition are key factors when looking at producing high quality replacement stock and making sure they have a good start in their first production cycle.

Pig resilience digs into DNA

Breakout sessions on pig resilience were hosted by John Harding from the University of Saskatchewan, Jack Dekkers from Iowa State University and Ben Willing from the University of Alberta.

Harding delivered the presentation, “The Natural Disease Challenge Model for Evaluating Resilience.”

A natural disease challenge model was established at a wean-to-finish research unit in Deschambault, Quebec in November 2015 to study disease. The model has provided a unique opportunity to intensively monitor disease transmission and expression.

The model has established that disease resilience traits like mortality, morbidity and performance have a sizeable heritable component, although the disease challenge is dynamic over time and not experimentally controlled. This demonstrates that improvement of disease resilience using genetic selection is possible, if appropriate measures of disease resilience can be obtained on animals within the high-health nucleus breeding farms.

The model has provided a unique opportunity to intensively monitor disease transmission and expression, and the effect of strategic interventions in a commercial research facility that has been managed consistently and systematically with well-trained staff over a four-year period.

Moving forward, large-scale public-private collaborative research partnerships will provide vital alternatives to improve pig health and welfare on commercial farms. This natural disease challenge model will play a role in that discovery.

Dekkers delivered the presentation, “Genetics and Early Predictors of Resilience.”

Infectious disease represents one of the largest cost components to the swine industry, incurring veterinary costs, loss of pigs due to mortality, reduced performance and reduced animal welfare.

Unique and extensive data has been collected on a large number of wean-finish pigs that can be used to understand the genetic basis of disease resilience and to develop genetic tests or indicator traits to identify pigs with high genetic merit for disease resilience, without having to expose them to disease. The latter is essential for the implementation of selection for disease resilience in nucleus breeding herds.

Genetic markers and genomic prediction provide a valuable tool to predict breeding values on animals for traits for which they are not being recorded. Disease resilience is a good candidate for this. Genomic prediction, however, requires ongoing recording of the phenotype in a so-called training population.

Willing delivered the presentation, “Host Microbial Interactions and Disease Resilience in Pigs.”

Gut microbiota has been identified as one of the important factors influencing disease resistance. Through a Genome Canada and Genome Alberta funded project, Willing has endeavoured to identify microbial populations associated with disease resistance and to characterize how disruptions associate with altered immune development in pigs.

The gastrointestinal tract of newborn mammals is rapidly colonized by environmental and maternal microbes with tremendous biomass and diversity. The relationship, balance and mechanistic interactions between these microbes in the gut is extremely complex and not well understood in states of health or disease.

Antibiotics may cause transient or persistent alterations in gut-associated microbiota and are suggested to be a major contributor to increased prevalence of immune mediated disorders. Since the gut microbiota – which consists of a dynamic community of bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea – is known to impact the development, maturation and function of the immune system, it is a natural extension that the microbiota will impact vaccine efficacy.

In humans, increased sanitation, reduced exposure to microbes in early life and frequent use of antimicrobials have been associated with an increased susceptibility to certain disease conditions. This can also be the case with swine production where different production methodologies and technologies are employed.

Smart technology’s integration challenges

Breakout sessions on smart technology were hosted by Dale Polson from Boehringer-Ingelheim Animal Health of Georgia, Chris Bomgaars from EveryPig Inc. of Florida and Benny Mote from the University of Nebraska.

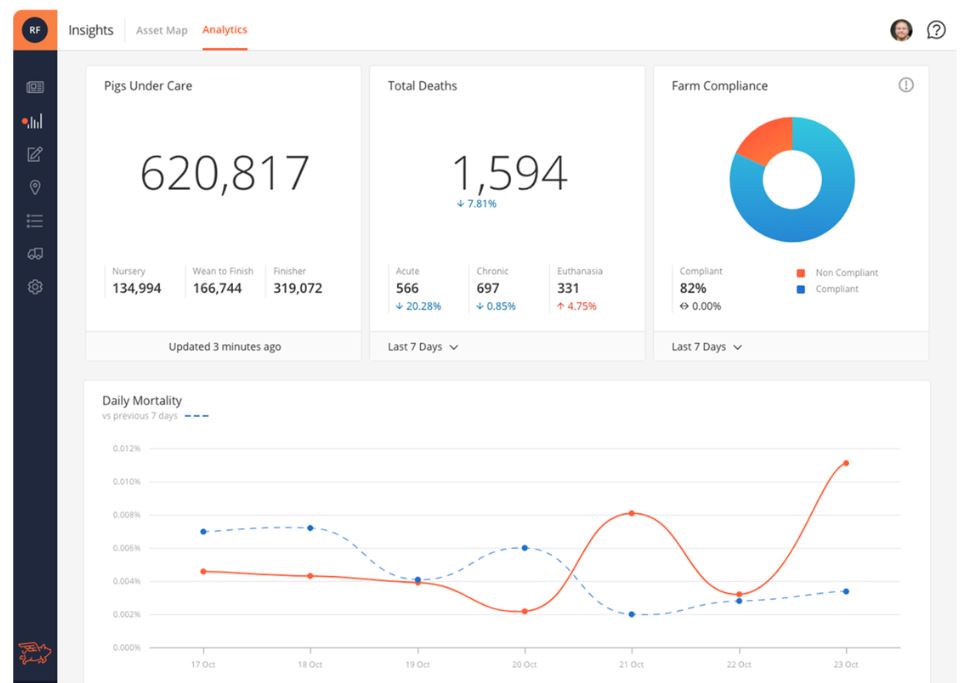

Polson delivered the presentation, “Precision Livestock Ecosystems: Integrating Technology, Process and Culture.”

Each precision livestock farming technology generally has value potential for any given farm site and thus can be evaluated to a degree in a similar manner as other products and services have always been and continue to be today. However, the greatest value of individual precision livestock technologies is not realized in isolation.

There are three primary elements to a strategic framework for all ecosystems that integrate and connect cyber-physical systems within any business environment: technology, process and culture. For all businesses and commercial operations that operate within each business environment, people are the drivers, technologies are the vehicles and processes are the roadways.

The potential of precision livestock farming technologies is clear. To continue to chase that potential and beyond, many existing as well as new start-up companies will enter the marketplace to supply these technologies to livestock producers. The challenge for these companies will be offering a clear value proposition for producers, related to effective integration and cost-consciousness.

Bomgaars delivered the presentation, “Reducing the Threat of African Swine Fever (and Other Severe Diseases) Through Telemedicine.”

Infectious disease outbreaks originating overseas have often been treated as someone else’s problem, unlikely to affect pork production in North America. As we have seen in recent years, the wait-and-see approach to the spread of disease among livestock may be an increasingly risky one.

The last 30 years have seen a shift to larger but fewer production operations. With this shift, efficiencies as well as the quality of the product have improved. Data collection and storage, however, still lag other industries.

The early detection of ASF is uncommon using the current methods available on-farm. As such, differential diagnoses are troublingly common. Barring the widespread adoption of portable laboratories, we can assume that early detection will continue to fall on the shoulders of on-site caregivers should the disease arrive in North America.

With the threat of ASF looming over the pork industry, it is more important than ever that producers adopt a structured data approach. The ability to spot the symptoms of ASF and other infectious diseases quickly may be the difference between containment and bankruptcy. Services like EveryPig provide structured barn-level data collection made exclusively for the pork production industry.

Mote delivered the presentation, “Individual Pig Activity Tracking in Group Housed Swine Offers a Deeper Understanding of Swine Production.”

Advanced detection and intervention of compromised pigs significantly increases the probability for recovery in addition to the potential for reducing disease transmission spread or subsequent injuries. To date, identifying sick or injured pigs is achieved through visual evaluation by caretakers and has practical limits as to the amount of time they can allot to monitoring each individual pig.

Application of precision technology has been slower to develop in the livestock sector than the crop sector due to the complexity of tracking individual animals. However, advances in technology has progressed to the point that the industry is on the cusp of a technology revolution.

As a means to address this need, Mote’s team developed and evaluated a deep feature-based detection and tracking platform, known as NUtrack Livestock Monitoring System, with the capabilities to automatically identify, maintain individual identification and continuously track the activities and location of group housed pigs. The system is built around consumer-level security camera hardware and desktop computers with graphics processing units.

During a 42-day trial, the overall accuracy of the system was shown to be greater than 99 per cent when pigs were not lying down. The unrivaled ability and accuracy of the NUtrack system contributes enormous promise in the advancement of precision livestock farming for swine.