By Bijon Brown

Editor’s note: Bijon Brown is the Production Economist for Alberta Pork. He is currently collecting and analyzing cost and pricing data to improve producer success. He can be contacted at bijon.brown@albertapork.com.

All business relationships contain a balance of power. In the western Canadian hog industry, over time, the power has swung from an equitable place for both producers and packers, to favouring packers and retailers.

Most will likely agree that a united front for producers is now more important than ever before to address the hog pricing situation. Concepts such as single-desk selling have largely gone by the wayside, as ambitious farmers more than two decades ago sought to outpace others around them, putting collective action aside in favour of high-octane capitalism. It was a good time to be in hogs, if you could compete, but since then, much has changed.

When the single desk was disbanded in Alberta, as an example, individual producers were now left to negotiate with a few packers, which became even more disproportionately skewed as the years went by. The tables have turned, and the negotiating power now resides with the packer. With very little government oversight on economic practices, packers have used this power to their advantage.

Packer power suppresses price

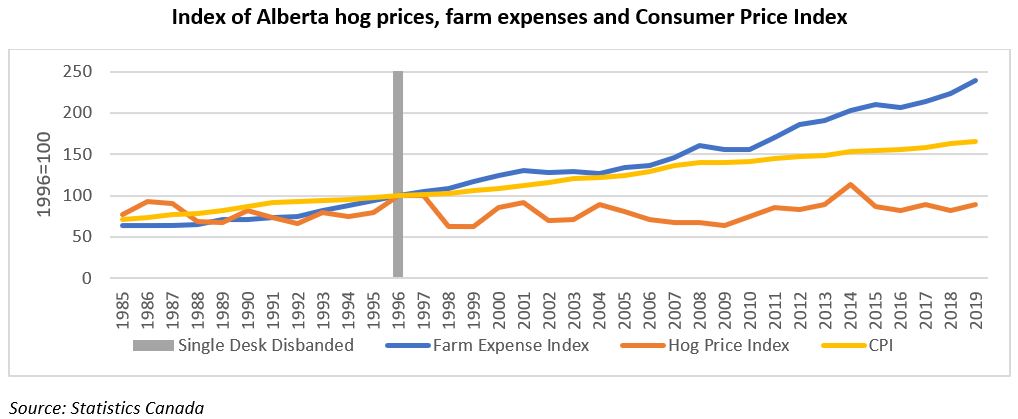

Cost of production is on the rise, along with overall inflation, but hog prices paid to producers have not increased. With the removal of the single desk, packers’ market power has driven down the ‘real price’ of hogs, which is the price that accounts for changes to the general cost of living. This has resulted in a considerably worse financial situation for producers.

In Alberta, the hog price index closely tracked the farm expense index until 1996, the year single-desk marketing ended. Since then, there has been a clear and growing divergence between the price and expense indices. Expenses in 2019 were more than twice what they were in 1996, while on the revenue side, the hog price in 2019 was lower than what it was in 1996. The same relative trend can be observed across the prairies.

With so few packers in western Canada, they can dictate the price in the contracts offered. Packers influence price through their ability to segment producers by individualizing agreements. This may be done by giving some producers more favourable rates or premiums than others based on volume, proximity or on any other desired basis. The inclusion of confidentiality clauses in contracts is also a component of market power. Market price uncertainty is generated because true prices are kept hidden. If producers cannot determine the true market price, how can they adequately negotiate better prices?

Improving prices requires greater unity

Negotiating power stems from producers’ ability to come together. The more producers are divided, the more power they give to packers, and the less control they have over prices.

How can producers unite? The notable and most effective option is to pursue the establishment of a single desk. Instead of being able to play hundreds of producers against each other, packers would need to deal with only one marketer that has producers’ best interests in mind, first and foremost.

The adoption of a single desk could shift the balance of power back to producers, resulting in a hog price that is more consistently favourable, though government support for this concept may be long gone. As an alternative to using the single desk, producers could consider coming together and forming marketing groups, some of which already exist.

A marketing group could sell and coordinate the distribution of hogs to the plants. For example, Hutterite colonies in Alberta currently make up more than 40 per cent of the industry’s core producers and own nearly half of all sows on-farm. If colonies were to form a marketing cooperative, then this could increase their bargaining power. Consolidated producer marketing means that a few packers would now be forced to compete on price for a larger volume from one source.

Packers’ economic model is driven by the number of hogs they can process in a day. Because they are still operating under-capacity in western Canada, the more hogs they can process in a day, the greater their profitability. If producers returned to collectively marketing their hogs, volumes would be more important to packers, and they would need to be competitive in their pricing to maintain their volumes.

Quebec pricing model shows promise

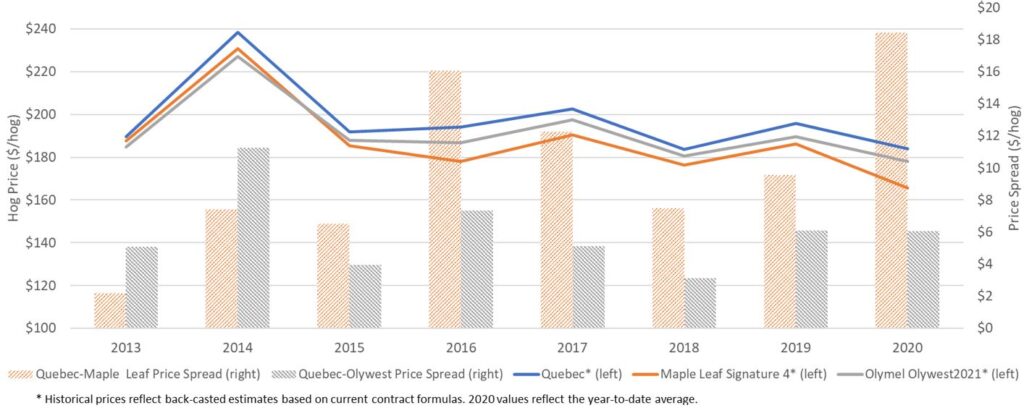

The Quebec pricing model is perhaps the best example we have in Canada of successful consolidated marketing power.

Hog price discovery in Quebec has been governed since the early 1980s by the Quebec Hog Producers’ collective marketing plan, where producers collectively negotiate a sales agreement with packers. The Régie des marchés agricoles et agroalimentaires du Québec, which regulates marketing plans in Quebec, recently upheld the previous cut-out formula in which the cash price can vary within 90 to 100 per cent of the cut-out price.

Two things have contributed to better prices in Quebec: single-desk marketing and an objective arbitrator to mediate the situation when there is no agreement between both sides. Provinces outside Quebec have neither a single desk nor an arbitrator. Having a single desk makes it possible for an arbitrator to review proposals from both producers and packers. When producers come together with one voice, they can create a better pricing environment.

Producer unity creates a platform for change

Greater producer power can lead to a more equitable share of value in the supply chain. With more power, producers can negotiate changes to contracts.

The main consideration in contract pricing is the source of base prices. Currently, hogs in Canada are priced based on U.S. hog prices, which U.S. packers are required to report to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). While the hog industries in Canada and the U.S. are integrated to a degree, pricing suffers due to this unnatural linkage, especially when political gamesmanship and trade disputes are considered.

U.S.-influenced hog pricing can be a detriment to the western Canadian producer if the numbers are manipulated. The main argument in favour of U.S. pricing is that Canada competes with the U.S. in the global market, so it makes sense to measure ourselves against this large competitor. The method works, but only if fair pricing and cut-out value are considered on an even playing field.

The North American pricing model is broken. U.S. price signals have been impacted by politics, government subsidies and continued structural change. A made-in-Canada pricing solution that incorporates our export differences may be the only sustainable way forward if U.S. signals continue to distort the picture.

Producer-packer unity strengthens the entire industry

While much attention is paid to the relationship between the producer and packer, a third player, the retailer, should not be forgotten when it comes to understanding price disparity.

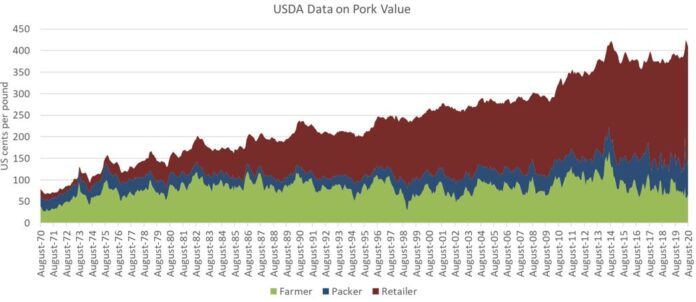

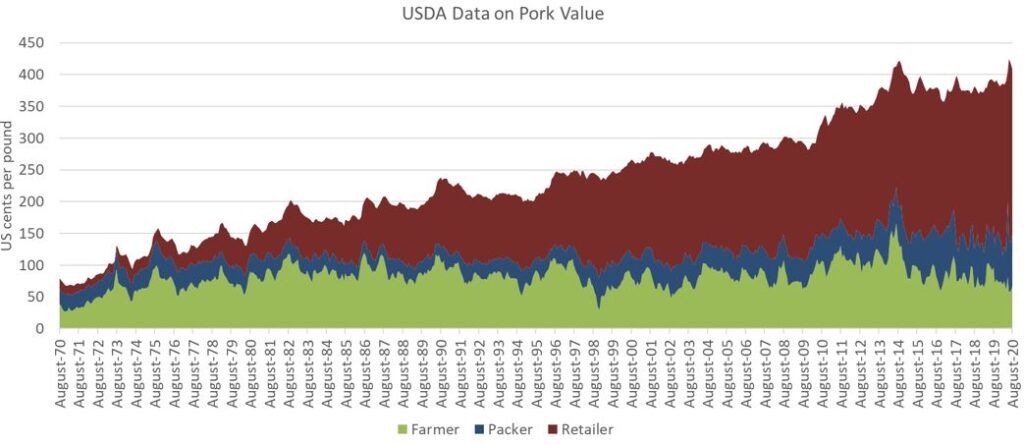

USDA data going back to 1970 shows how, despite predictable market fluctuations for producers and packers, on the retail side, value for pork has shot up nearly 500 per cent, which is not consistent with the price for pigs or wholesale pork. While the U.S. system is fundamentally different from how we should measure ourselves in Canada, it is the best existing benchmark we currently have.

In 2019, most American farmers received less than $1 per pound for their pigs, while processors received nearly $1.50 per pound of wholesale pork. Meanwhile, retailers received close to $4 per pound for packaged pork sold in-store, and consumers have been paying upwards of $8 per pound, in some cases, to take that product home. The situation in Canada is very similar in that regard.

Nearly six per cent of product found in retail meat cases is wasted at the store level. This means, of the $4 retail price, approximately $0.24 is discarded. It may not seem like much, but if we could eradicate the waste and spread this benefit across the value chain, producers could receive almost $12 more per hundred kilograms of meat produced if just $0.04 of that $0.24 was passed back to producers, with the remaining savings benefitting other stakeholders.

What would drive such an incentive for change? One such impetus comes from producers and packers working together to lobby for consumer buy-in, as eliminating waste is known to be a consumer concern. Consumers should consider where their meat originates and whether their dollar is going to the right place – to pay hard-working Canadian farmers for the end-product that is possible only because of a longer-term commitment to raising pigs.

Taking the next steps toward fair pricing

When it comes to generating positive change across the value chain, greater producer action and packer collaboration are needed.

Producers need to ask: What steps do I need to take to shift the power back to an equitable place for both producers and packers?