By Andrew Heck

Rallying the troops can be difficult when the enemy is mostly unseen, poorly understood or perhaps not even viewed as a threat. But rallying the troops to further the cause of wild boar eradication in Canada is long overdue.

Still, the Canadian war on wild boar continues to lack awareness among many people, even within the swine industry. The growing problem of invasive, non-native wild boar at large has been plaguing farmers and landowners since at least the 1980s, and today’s population remains an under-studied, complex and deeply dividing problem. While some stakeholders are not yet on the side of swift, tangible action toward the goal of removing this species from our midst, they certainly should be.

The eradication of wild boar is a desperate and challenging but entirely necessary mission. For hog producers, much work must be done to mitigate the spread of swine diseases to domestic pigs, including the sizeable, high-value commercial herd. For cattle ranchers, protecting pastures from rooting is a priority; for crop farmers, defending fields from being eaten from the inside-out; and for ecologists, preventing widespread environmental degradation.

Beyond the specific impacts of wild boar on their surroundings, a much more significant risk is posed by their presence: the potential for transmitting diseases like African Swine Fever (ASF) – which would practically end Canada’s global trade in pork – along with Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) – which would pose an incredibly challenging health scenario for the commercial hog and cattle herds.

Untold harm could be on its way if the war on wild boar is lost. But collectively, we have barely begun to make an advance. Who will step up? A few prominent stakeholders are leading the charge, but more are needed.

Eradication is the only solution; anything else will certainly fall short and seriously threaten Canada’s multi-billion-dollar pork and beef industries if foreign markets shut their doors to Canadian meat exports, which they certainly would, if the existing precedent holds up. This is not a gamble anyone should be willing to take, but yet, the dice are still being rolled, with Canadian farmers standing to lose everything they have worked their lives for, and Canadian consumers standing to lose the quality-assured, safe, nutritious products they know and love.

If it sounds more serious than you thought, it is.

Battling boar with bushcraft

At a meeting of the Alberta Pork board of directors in late 2020, it was decided that more than $400,000 would be committed toward wild boar eradication and related disease prevention efforts – a bold and courageous throwing down of the gauntlet by Alberta producers.

“The commitment of funding from our board was instrumental in helping our organization support two consultants to track, trap and kill wild boar,” said Charlotte Shipp, Industry Programs Manager, Alberta Pork. “Thanks to this funding, combined with support from our provincial government and other partners, Alberta is taking an aggressive and hardline stance on eradicating wild boar at large.”

The consultants, Larry and Scarlett, are two individuals hot on the trail of Alberta’s wild boar. With strategic direction from Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, these troopers have taken the fight of this destructive, elusive species straight into the battlefield where the formidable creatures make their stand.

Larry and Scarlett’s covert operational tactics are well-suited to the work they do. Wild boar are extremely intelligent and driven to survive, which can make them very unpredictable.

“If you hurt one of them, they won’t stop until either you’re dead or they’re dead,” said Larry. “That’s just the way it is.”

The traps set by Larry and Scarlett are found in several strategic locations more than 100 kilometres northwest of Edmonton. Because much of their work takes place on private land, establishing relationships with locals is a necessary component of the job.

“Our biggest reward is getting to know landowners and sharing the joy and satisfaction after we have removed a sounder [group of wild boar] from their property,” said Scarlett. “Larry and I are a husband-and-wife team, and we own land ourselves, which helps them identify with us a bit better, I believe.”

Trust is key when operating on private land, not only to gain access to relevant sites, but also for the maintenance of pricey equipment. In terms of choosing where to set traps, much of the intel relies on Larry’s depth of experience in the bush.

“You have to look for patterns – almost like boar ‘highways’ – to determine where they may have been, where they may be now, and where they may be going next,” said Larry. “They’re so smart that it’s incredibly difficult at times. Probably the only animal out here that comes close to their intelligence is a wolf.”

If intelligence and stubbornness are positive signs for the survival of a species – even an invasive one – then wild boar are masters of their adoptive domain.

“You can really see where they’re going in winter, but the conditions for us can be brutal,” said Scarlett. “A lot of our equipment suffers because of this. In summer, we get about three weeks of battery life for our traps and cameras, but in winter, they have to be recharged and replaced almost weekly.”

Each site includes a purpose-built trap and two tracking cameras, one of which is mounted at eye level tens of feet away from the trap’s gate, and the other of which is mounted up high on a nearby tree, peering into the trap itself. The tree-mounted camera essentially allows Larry and Scarlett to deliver the final verdict on any given trap – often from the ‘comfort’ of their own bed, usually between the hours of 11 p.m. and 5 a.m., seven days a week.

The cameras operate using cellular data transmitted when a passing animal triggers a sensor, which sends a notification to the couple’s mobile phone. Even in the middle of the night, they have to work quickly to make the call on whether to send the signal back to the trap for the gate to close. This is only done when they can see an entire sounder inside of a given trap. Otherwise, if even one individual is observed outside the fence, closing the gate could botch the entire operation.

“The sows and juveniles absolutely have to be in the trap,” said Scarlett. “We won’t drop the gate until we are sure the complete sounder is inside, which can take weeks or months depending on how eagerly a particular sounder enters the trap. If we drop the gate with individuals still outside, we end up educating them, which makes our job way more tricky.”

Each sounder numbers approximately 10 to 15 individuals. Females – which compose about 70 per cent of any sounder – will farrow litters of six to nine juveniles twice annually, starting when they reach reproductive maturity at six-months-old. Eradicating an entire sounder, in that case, could represent upwards of 100 individuals removed from an area for that given year. Ensuring that traps are capable of doing the job right is a key concern.

Boars are notably confident in the presence of fellow wildlife – even bears – which creates two challenges: convincing a sounder to enter a trap willingly, and also keeping bears away from the bait that is meant for boars. The bait is a corn-based proprietary mixture concocted in Larry and Scarlett’s own basement through trial and error.

Larry and Scarlett’s work is largely thankless and unknown, except among the landowners with whom they have forged friendships beyond the scope of their boar-based efforts. Such is the case with one landowning couple living near the intersection of where an unpaved road meets a relatively perpendicular river – on the edge of nowhere, to most outsiders.

The landowners have lived in that spot for more than four decades, and only within the past couple of years did they gain first-hand experience with wild boar when a ruthless sounder tore a shocking path of destruction through their cattle pasture and barley crop. Like many of their neighbours, the landowners previously had little idea just how dangerous the boars could be.

“It’s not only land that’s affected but livestock too,” said Scarlett. “We’ve heard from landowners about their cattle having abortions due to the stress of noticing wild boar in the area. And who knows if a boar would ever attack a calf? They wouldn’t hesitate to eat just about anything convenient, including meat.”

Skepticism contributes to a widespread misunderstanding or downplaying of the issue. In 2008, the Government of Alberta issued a bounty on wild boar, and to this day, many avid hunters would love to come across one to shoot, with no need for a tag. Unfortunately for hunters, the bounty system essentially failed and, in fact, worsened the problem altogether. For this reason, the practice of hunting wild boar in Canada is expressly discouraged.

And it is not just wild boar hunting, but hunting in general, that complicates eradication. As fall approaches, and plentiful summer food stocks begin to run dry, boars have a habit of going into hiding, combined with the encroachment of hunters who are seeking other forms of game.

“It’s like a faucet turns off,” said Scarlett. “As soon as hunting season begins, we notice a dramatic reduction in activity on our cameras. They become even harder to track.”

Despite the potential for conflicting viewpoints on hunting, Larry stressed that it is not an us-and-them mentality.

“I have nothing against hunters, and I’ve hunted my whole life,” said Larry. “The sites that receive the most pressure from hunting are the same sites where we tend to eradicate the most wild boar. It’s no coincidence; anything short of whole sounder removal increases the wild boar population.”

Looking at the bigger picture, Larry sees potentially negative consequences if the problem persists.

“We just want to do everything we can to contribute to the success of the program,” said Larry. “We really have to stop the spread of wild boar. If we don’t, we’re all going to suffer for it. If farmers have to deal with this situation while trying to produce food, it’s going to be felt all the way to the grocery store.”

Swapping war stories with a veteran

Perry Abramenko is an Inspector & Pest Program Specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry who has been working since 2013 on the wild boar file.

“The bounty program did not accomplish what it was supposed to, in terms of getting rid of boars, but it did give us a lot of data to work with,” said Abramenko. “With any kind of human disturbance, these animals scatter and infest new areas. They’re so intelligent, and they’re nocturnal, so they know where they can be safest.”

The data collected through the bounty program suggested in 2013 that the problem was more noticeable in some municipalities than others, but the prevailing belief since then is that sightings are simply under-reported. While certain municipalities may have a higher concentration of observed wild boar, that is an insufficient way of gauging the scope. According to Abramenko, 24 of Alberta’s 74 rural municipalities have reported at least one wild boar sighting – a much broader range than only two eradication specialists can handle on their own.

“Those sightings are the ones we’re aware of. Are there others?” asked Abramenko. “There certainly could be. This is why reports from the public are so vital.”

Around the time of Abramenko’s hiring, the Alberta Agricultural Services Boards’ provincial committee – which directs the province’s 69 municipality-based farming regions – passed a resolution that has provided the pretext for implementing stronger measures against wild boar.

From north to south, at least 10 of Alberta’s rural municipalities today have passed bylaws banning wild boar, including the counties of Spirit River, Grande Prairie, Lesser Slave River, Smoky Lake, Thorhild, Yellowhead, Wetaskiwin, Stettler, Red Deer and Cardston. But that still covers fewer than half of the locations where the animals have been spotted and, curiously, few of the acknowledged hotbeds.

“In addition to supporting the work of Larry and Scarlett, with Perry’s help, Alberta Pork will be pushing for all rural municipalities in the province to ban wild boar,” said Charlotte Shipp, Industry Programs Manager, Alberta Pork. “If we don’t have the law on our side, we are placed into a major predicament. We will ask municipal representatives to assist us on this; otherwise, landowners in their communities will be affected.”

Novel, cross-ministerial approaches are also being examined. Partnering with Alberta Environment and Parks, work is being done to train invasive-mussel-sniffing dogs to detect wild boar scat. The same biologists behind the sniffing project are also collecting water samples from the province’s lakes to detect the presence of wild boar DNA, as another means of surveillance. By analyzing water samples, further hints could be given, and by using drones to survey land and crop damage, there is no shortage of techniques being explored or opportunities to enhance efforts, if appropriate resources are made available.

“The sooner you get onto eradicating a pest, the likelier you are to be successful,” said Abramenko. “If you can get onto them when it’s an emerging population, when the densities are not very high, that’s ideal. That said, I think eradication is still achievable, as long as we stay the course.”

The larger, farther-reaching goal has extended toward establishing a permanent program involving wildlife groups.

Taking a fresh approach to the frontline

As time goes on, new regiments continue to join the alliance against wild boar, including the Alberta Invasive Species Council (AISC).

“We wanted to take the wild boar issue and make it very public,” said Megan Evans, Executive Director, AISC. “It took a long time, but we carefully crafted messaging to be broadcasted through various forms of traditional and online media.”

With assistance from Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, Alberta Pork and Alberta Beef, AISC’s ‘Squeal on Pigs!’ campaign has received a great deal of attention on social media, and the organization has been sought after by mainstream media outlets as well, further amplifying the campaign’s reach.

“It started when I got a hold of officials in the U.S.,” said Evans. “That’s where we got the ‘Squeal on Pigs!’ concept from – we actually borrowed and adapted their materials, which fit perfectly with what we are trying to do.”

Not everyone is entirely happy with the push toward eradication, however. As with many issues touching animal agriculture, an open online petition, ‘Stop Mass Extermination of Wild Boars,’ has been circulated on the website, ‘Animal Petitions: Humans Defending Animals From Other Humans.’ The petition has received nearly 20,000 virtual signatures from individuals who may or may not be from Alberta or even Canada.

“It’s incredibly disappointing that some members of the public insist that our collective efforts toward eradication and awareness are not the right course of action,” said Darcy Fitzgerald, Executive Director, Alberta Pork. “It represents a total disregard for the farmers who produce food for Canadians and the natural ecosystem this invasive species is infringing upon.”

Unmoved by critics, Evans is pushing forth and encourages anyone and everyone interested in joining AISC’s efforts to do so.

“We’re hoping to make this campaign even bigger,” said Evans. “Billboards, hats, t-shirts – just about anything to spread the word. That’s what we’re all about.”

What is the best way to report a wild boar sighting in Alberta? AISC’s free ‘EDDMapS’ smartphone app is a convenient way to provide the necessary information to Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. Alternatively, sightings can be reported by emailing af.wildboar@gov.ab.ca or by phoning 310-FARM (3276).

Understanding the art (and science) of war

Invasive species management is also a focus on the national level for the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC). Working with the National Farmed Animal Health and Welfare Council (NFAHWC), the two organizations are collaborating to help facilitate knowledge sharing and coordinate mitigation efforts across Canada, with connection to the Canadian Pork Council’s (CPC) African Swine Fever (ASF) Executive Management Board.

Environment and Climate Change Canada has endorsed the CWHC to lead a project that supports mitigating the social and ecological harm created by wild boar. As a starting point, the group performed a scan of wild boar prevention efforts for each province. After that, strategic and operational working groups were formed. The strategic approach includes hosting a webpage of wild boar resources, in addition to a communications approach that directs public awareness efforts through social media. A disease surveillance sub-group has been tasked with developing a national sampling protocol for wild boar and the establishment of a central tissue repository. If implemented, the tissue repository would store samples to support research and testing by independent investigators.

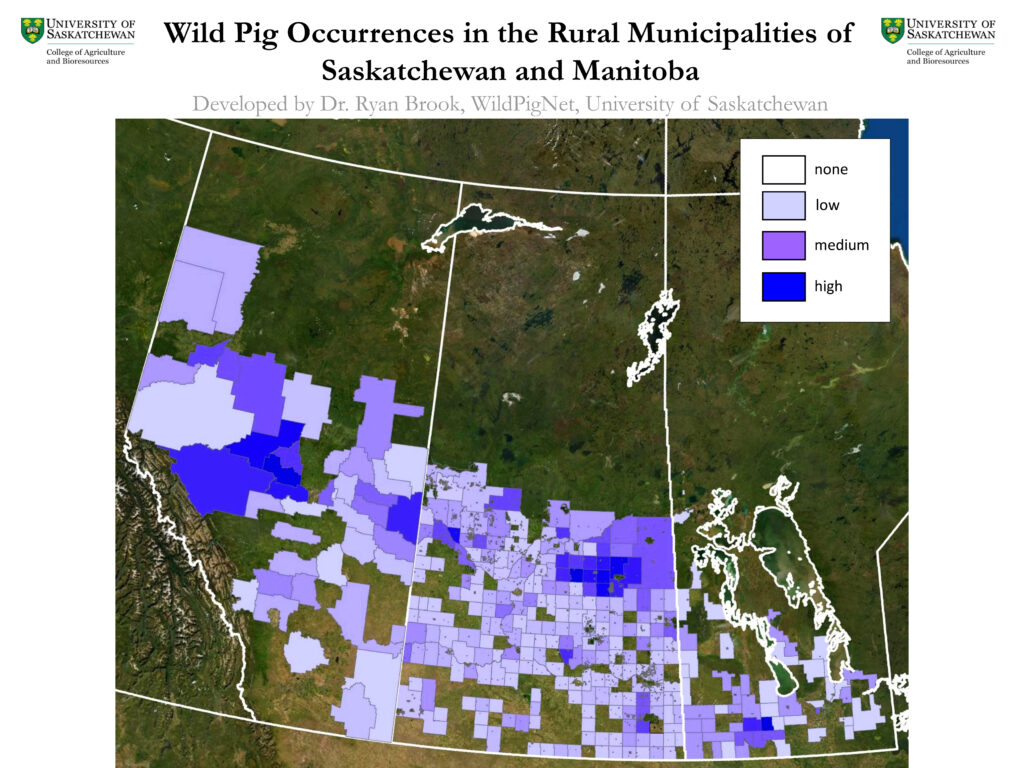

Before being able to understand the disease implications of wild boar, the industry first has to establish where they are. Ryan Brook, a researcher at the University of Saskatchewan, has been observing the problem for more than a decade. Try as he might, adequately expressing the gravity of the situation has been a struggle for Brook, whose persistent efforts to study the spread of wild boar and raise alarm bells have been met with some resistance.

“For the first eight years I did this work, everyone ignored me, and for the next two, everyone yelled at me, but now it’s slowly changing,” said Brook. “No-one benefits from having wild pigs around, which means there’s a ton of common ground to work together, if we choose to.”

In 2019, Brook and his PhD student, Ruth Aschim, released a comprehensive map of wild boar – a great start at capturing the extent of the invasion, given the inconsistency and inattention to reporting sightings and truly investing in understanding the issue.

“It’s important that we have useful and scientifically defensible work,” said Brook. “Without it, we’re not too sure if we’re making a significant difference. Sometimes I think eradication efforts are a bit like mowing the lawn – we’re dealing with it the best we can, but the populations rebound so quickly. We don’t really know unless we have the data.”

When it comes to persuading deniers – those who believe the crisis is being overblown – Brook thinks appealing to the pocketbook may be effective.

“The economic impact needs to be studied better,” said Brook. “We know about compensation for crop losses, as an example, but what about the cost of disease? Is it worth the risk?”

Supporting Brook’s theory, a study released in July 2021 from the University of Queensland (Australia) and University of Canterbury (New Zealand) has used predictive population models and advanced mapping techniques to suggest that wild boar may be responsible for rooting an area covering a total of 36,000 to 124,000 square kilometres in regions of the world where they are not native. The result is the release of around 4.9 million metric tonnes of carbon dioxide annually, which is the equivalent of 1.1 million fossil-fuel-burning motor vehicles. Another study out of Australia, measuring the financial impact of pests over the last six decades, suggests invasive mammals, including wild boar, may have cost the country $66 billion during that span of time.

From their massive expansion efforts to their outright destructive behaviours, in addition to what we area learning about their impact on carbon emissions and the economy, wild boar present a ballooning challenge for ecologists to convince policymakers to take meaningful action.

The standoff south of the border

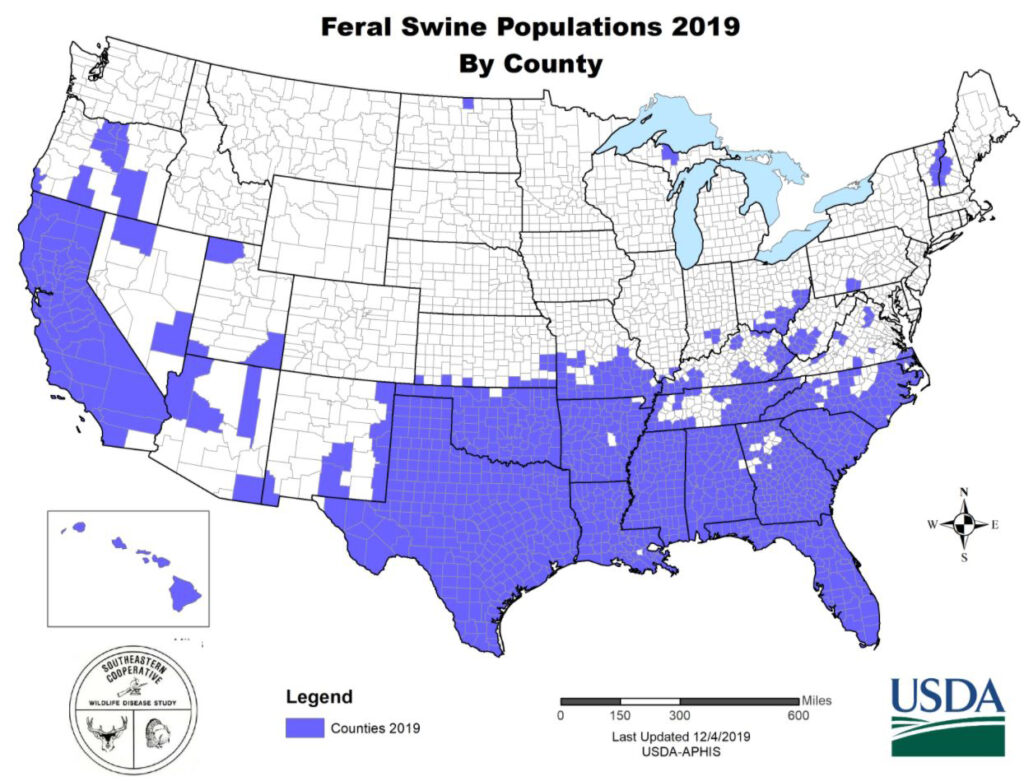

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) standard nomenclature for wild boar is ‘feral swine.’ In 2014, in response to the increasing damage and disease threats posed by expanding feral swine populations, U.S. Congress appropriated $20 million to the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) for the creation of the collaborative ‘National Feral Swine Damage Management Program.’ Congress has continued to allocate funds annually, in support.

Through testing feral swine carcasses recovered from across the country, USDA-APHIS monitors for African Swine Fever (ASF), Classical Swine Fever (CSF), Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD), pseudorabies and swine brucellosis. To date, feral swine blood samples have been seropositive for pseudorabies and swine brucellosis, but, thankfully, no cases of ASF, CSF or FMD have been identified. These afflictions are all critically concerning for the commercial swine industry, making this testing an invaluable part of surveillance efforts. Recently, USDA-APHIS and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) reached an understanding regarding a protocol to maintain cross-border trade between our countries in the case of an ASF outbreak in wild boar on either side of the border – a positive development, however cynical seeming.

“These animals don’t respect ranch fencing, county borders, state borders or international borders,” said Justin Bush, Executive Coordinator, Washington Invasive Species Council. “Our challenge is finding the best ways to engage the public and motivate them to participate in feral swine reporting. The mantra is, ‘Squeal on Pigs!’ If you see something, say something.”

In 2017, the state of Washington conducted a study to measure the potential economic impact of feral swine when it comes to harming crops and livestock. Following the study, the total price tag was estimated at more than $6 billion worth of agricultural commodities at stake.

“Any time humans play a part in invasive species trends, it becomes very unpredictable. That’s the hardest thing to grapple with,” said Jeanine Neskey, Extension Specialist, USDA-APHIS. “Genetics samples are helping us understand where pigs are moving to and from. We can tell that pigs found in one area are directly related to populations found hundreds of miles away, which suggests people are moving them intentionally. In some cases, law enforcement has caught offenders, and they’ve been prosecuted, but that’s rare.”

In Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and Florida, feral swine are present in all but a small handful of counties, and they are on the move in Canada’s direction. Missouri, sharing its southern border with Arkansas, is at a crossroads. Directly north of Missouri sits Iowa – a major commercial pork-producing and -processing region with little to no natural fortifications to stem the spread. Beyond Iowa, Minnesota and Manitoba.

“We still have a lot of work to do to get people to realize the problem,” said Neskey. “Everyone should care if feral swine are running your local farmer out of business.”

Rolette County, North Dakota, is the only U.S. jurisdiction along the 49th parallel where any population of feral swine was known to exist in 2019. The county is adjacent to Turtle Mountain Provincial Park in Manitoba, directly south of Brandon. In the northeastern U.S., target areas exist near the Vermont and New Hampshire borders with Quebec, just south of Sherbrooke.

In 2015, a study conducted by USDA-APHIS revealed that nearly 50 per cent of more than 300 samples collected from feral swine carcasses processed at Texas abattoirs contained antibodies for Leptospira – the bacteria responsible for Leptospirosis in animals and humans. Without treatment, Leptospirosis can lead to kidney damage, meningitis, liver failure, respiratory distress and even death. Just the presence of Leptospira at an abattoir puts workers at risk, not to mention consumers.

Feral swine presence, worsened through hunting, routinely jeopardizes the safety of motorists in Texas as well. Vehicle collisions with these animals can occur year-round, 24 hours a day, with nighttime during the fall and winter months presenting the greatest risk. In some cases, motorists have died as a result of these crashes, which, collectively generate $36 million worth of personal and property damage annually.

In a landmark, progressively minded decision, in 2015, Montana became the first U.S. state to declare wild boar hunting illegal. Since then, keeping wild boar at bay has been a focus for the state, and no major concerns have emerged since then, as a result.

In contrast, in 1999, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency attempted to control wild boar by opening a statewide hunting season with no tags or bag limit. Unfortunately, it was during this period that their numbers grew rapidly, as disjointed populations began to occur in areas of the state where they had never existed before. Recognizing its gaffe, the state shifted gears in 2011, declaring wild boar an invasive species, rather than wild game – partly acknowledging its mistake but not fully rectifying it.

The Montana-Tennessee dichotomy represents a tale of two states: one confronting the matter before it is too late, and one being dismissive of the matter until the window of opportunity has closed. It is a slippery slope and an uphill battle for champions of eradication.

“Everybody has a role to play, but they might not be aware of it,” said Bush. “I believe we can eliminate feral swine, but it is going to take the whole community from agriculture and government to Indigenous groups and foresters.”

Saskatchewan and Manitoba offer backup, urge unity

In Saskatchewan, where the range and concentration of wild boar have received considerable academic investigation, producers too are taking note.

“We’re still trying to understand the full extent of the problem. We’ve known for years about some areas where wild boar might be living but finding evidence of exactly where has been challenging. Property damage of any kind is a concern,” said Mark Ferguson, General Manager, Sask Pork. “It’s also a high priority for our board on the disease side. We fully appreciate the need for vigilance, since there’s still a significant risk that’s not worth taking.”

The Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation (SCIC) conducts eradication efforts through its ‘Feral Wild Boar Control Program,’ based on reported sightings mostly from observant landowners. In some cases, insurance payouts have been made directly linked to crop damage caused by wild boar. In the past two decades, Moose Mountain Provincial Park in the southeastern part of the province attracted interest.

Saskatchewan Agriculture also has a surveillance program, run in cooperation with SCIC, with camera-equipped bait stations placed in areas where sightings have been reported and in areas close to farmed wild boar operations. To date, more than 40 bait stations have been established. Currently, attention is being paid to the Lenore Lake region in the north-central part of the province – home to a wildlife area and bird sanctuary – where more than 500 wild boar specimens have been removed in the last five years.

“We are asking the public not to hunt these animals and report them instead,” said Ferguson. “Because hunting can contribute to the problem, the best course of action is to report sightings to the 1-833-PIGSPOT hotline in Saskatchewan or to the nearest SCIC office.”

Recognizing the growing need to act, Manitoba Pork has looked to Alberta Pork as a guiding example for how to approach the issue.

“There are differences with each jurisdiction,” said Darcy Fitzgerald, Executive Director, Alberta Pork. “If we want the program to work, we need coordination across the country, and we need to have resources from all levels of government to target our programming.”

Currently, Manitoba Pork is seeking support from the provincial government to provide funding for activities that would kickstart an eradication campaign where one does not already exist.

“We went to our board of directors and presented the problem,” said Jenelle Hamblin, Manager, Swine Health, Manitoba Pork. “They saw what’s going on in other parts of the world, and their response was, ‘There’s no way we can let that happen here.’ They know it would be a huge detriment to our sector.”

In Manitoba, much of the known wild boar sightings have occurred on the periphery of the Manitoba Escarpment – a wooded upland region where bush meets agricultural land. The region contains Riding Mountain Provincial Park and Spruce Woods Provincial Park. Hamblin suggests that this area of the province could start attracting wild boar if care is not taken.

“Wild pigs can harm our domestic swine herd and trade in pork, and that’s a problem. They can harm crops, and that’s a problem. They can harm the environment, and that’s a problem,” said Hamblin. “The common denominator is that, if they’re gone, they don’t pose that risk anymore. This is why we all need to work together.”

The current proposal from Manitoba Pork includes a collaboration with Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development, along with wildlife groups in the province, to assess a range of strategies that could be employed for eradication.

In Manitoba, wild boar sightings can be reported by emailing wildlife@gov.mb.ca or by phoning the nearest Manitoba Conservation and Climate office.

Ontario allies with the West

While the wild boar issue in Canada is mostly contained to the prairies, in Ontario, new support to address the problem is coming, thanks to an increasing sense of anxiety and awareness of how easily their populations can spread.

In April 2021, the Government of Ontario issued a draft proposal for review: ‘Ontario’s Strategy to Address the Threat of Invasive Wild Pigs.’ which calls for clear communication, robust policy, management action and strong collaboration between government agencies to address the threat of wild boar in the province.

“We are currently considering input that we received to finalize the strategy,” said Bree Walpole, Senior Policy Advisor, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Services. “Wild pigs are not established in Ontario at this time, and we aim to keep it that way.”

As in Alberta, the plan recognizes the serious threats attributed to the spread of wild boar, and it touches on the impact to relevant stakeholder groups, like Ontario Pork. Ontario’s plan also suggests a ban on hunting wild boar, using a regulatory approach under the province’s Invasive Species Act. The amendment would still allow landowners to kill wild boar to protect their property from damage, including biosecurity reasons. In addition to directly addressing the issue of hunting, the Ontario plan also takes aim at wild boar in captivity.

“We want to make sure support is available to anyone who needs to transition,” said Stacey Ash, Manager, Communications and Consumer Marketing, Ontario Pork. “Farmed wild boar poses a risk, but we recognize the need to assist those farmers who will need to phase out these kinds of operations.”

In Ontario, wild boar sightings can be reported by emailing info@invadingspecies.com or by phoning 1-800-563-7711.

No armistice in sight

With relatively weak and inconsistent communication and leadership dominating the discussion around wild boar to this point, the Canadian pork industry will have to remain stationed in the trenches, as wild boar continue to roam. In fact, the firefight may be only just beginning.

While some strategic partners have been providing munitions support, others, sadly, continue to look on from afar with doubt. Learning the hard way may be the unfortunate but inevitable result, in some cases, and all cooperative stakeholders should take note and work to rally the critics within the industry to become supporters. Without all stakeholders on the same page, every link in the value chain can be considered at-risk.

With the news of African Swine Fever (ASF) arriving in the Dominican Republic and Haiti, foreign animal disease threats remain the chief concern of the commercial hog industry in North America. It is incumbent upon those within the industry and government to support greater action to combat wild boar, and it is everyone’s responsibility to take a stronger stance on this issue.

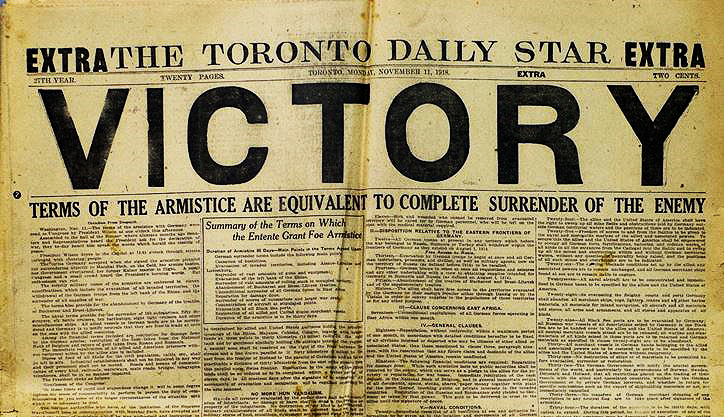

What will it require for our country to be able to declare victory on wild boar? Before we get too far ahead of ourselves, it starts with an honest recognition of the task at hand. It is gut-check time, and we have to hit the ground running.

Through research, eradication attempts and public campaigns, we have to examine all angles of this hairy, audacious goal. And while the industry is generally moving in a unified direction, enlisting additional soldiers will be the key to winning not only the latest battle, but the larger war on wild boar in Canada.