By Lexie Reed

Editor’s note: Lexie Reed is a food animal veterinarian based in Lethbridge, Alberta. She can be contacted at lexiereedvm@gmail.com.

The impact of transportation on animal health and welfare remains a hot-button issue for the livestock industry. All livestock systems require live animal transport at some point in the system. Further, transportation is the event in which the public is most likely to see and interact with animals in the food system.

The health and welfare effects of this commonplace event are not well understood in many food animal systems, including the practice of transporting weaner pigs. Federal transport regulations in Canada limit the transport time of pigs to 28 hours. These regulations are based mainly on research on market hogs, not weaner pigs, which differ physiologically.

New research, led by animal behaviour expert Jennifer Brown of Prairie Swine Centre, supported by Swine Innovation Porc, aims to assess the response of weaner pigs under Canadian commercial transport conditions. Brown, in collaboration with animal scientists at the University of Saskatchewan and University of Guelph, investigated physical and behavioural responses of weaners after short- and long-distance transportation.

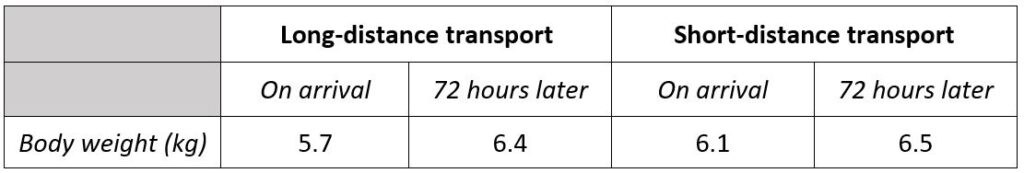

Brown found that weaners subjected to long-distance transportation lost more of their body weight, experienced more dehydration and spent more time feeding, drinking and sitting after the journey than weaners transported short distances. However, weaners transported shorter distances had more muscle injuries and higher indicators of physiological stress, as evidenced by blood cortisol- and blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios.

Prairie Swine Centre’s research report states: “In conclusion, this study represents the first research in Canada on the effects of transport on weaner pig health and welfare. Differences in long-distance and short-distance transport were found, but neither treatment was identified as being better than the other.”

Better adaptation takes longer

In this study, short-distance transportation was defined as less than three hours of duration. The piglets transported short distance were weaned at the same time they were shipped. Long-distance transportation was defined as being greater than 30 hours of duration, and in contrast, the piglets in this group were weaned several days before transportation occurred.

While it might at first seem counter-intuitive that the weaners transported a shorter distance had higher indicators of physiological stress and muscle injury, Brown believes that the weaning time, as well as adaption to transport, contributed to this difference.

“Short-distance piglets were weaned and transported at the same time, so their response post-transportation reflects acute stress,” said Brown. “Because long-distance weaners had a much greater transport time, they habituated to transport conditions and showed reduced levels of stress biomarkers on arrival compared to short-distance weaners. It appears that the long-distance weaners adapted reasonably well to transport, as they did not clearly show signs of chronic stress.”

While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly where acute stress turns into chronic stress, or where habituation occurs, Brown’s findings suggest that weaners may be adapting to transportation conditions during the added time in long-distance transport.

All pig transportation in Canada is mandated by the Health of Animals Regulations under the Health of Animals Act. Transporters and producers are held legally responsible under this legislation. Pig transportation is also regulated by the National Farm Animal Care Council’s (NFACC) Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pigs. While the pig code is not law, on-farm and transport quality assurance programs closely align with this standard. For more than 99 per cent of pigs raised in Canada, entering into abattoirs inspected by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), quality assurance guarantees are required.

To pass the Animal Care Assessment (ACA) section of the Canadian Quality Assurance (CQA) or the PigCARE component of the Canadian Pork Excellence (CPE) program, producers must meet the requirements within the code. As such, updates to the code are introduced only following consultation with animal welfare experts. Research such as this project by Brown is designed to eventually find its way into industry standards, which are adopted with public trust and the confidence of international trading partners in mind.

Pre-weaning prior to shipping may have positive effects

While still in the early stages of weaner transport research, Brown thinks this work could impact the industry in three ways. The first potential impact could be the separation of weaning and transportation events at the farm level.

“Especially for long transport, so that pigs are recovered to some extent from weaning and consuming feed before they are transported,” said Brown. “This would require that sow barns have nursery space to wean into.”

The other impacts concern trailers.

“These results could influence the use climate-controlled trailers, with forced ventilation or insulation, especially in extreme hot or cold temperatures,” said Brown. “The provision of feed, water and rest on trailers is another consideration.”

However, Brown cautions that more research would be required in this area before any of those changes could be applied. By further enhancing the industry’s understanding of weaner transportation, changes to these practices are almost inevitable, thanks to the support of scientists, veterinarians, government and other stakeholders.