By Caitlin Gill, Trenna Brusky & Heather L. Wilson

Editor’s note: Caitlin Gill is Communications Coordinator, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO). She can be contacted at caitlin.gill@usask.ca. Trenna Brusky is Marketing Coordinator, VIDO.

Immunization helps prevent and control infectious diseases and reduces associated economic loss in livestock industries. Innovative immunization strategies provide producers with more effective and efficient ways to protect their animals. These innovations include new vaccines that offer broader protection and new delivery methods that reduce stress on the animals, minimize the need for handling and remove the use of needles to protect the health of the animal and the barn staff.

Dr. Heather L. Wilson, a research scientist at the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO), has spent almost two decades developing vaccines to protect breeding pigs from reproductive diseases and piglets against infectious diseases. Her team is now looking at the technical feasibility of intrauterine immunization – a possible breakthrough that could change the way female pigs are vaccinated, offering new solutions to existing disease issues like porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED).

Modern systems require new approaches

The industry transition to group housing and farrowing systems in Canada will require a shift in standard vaccination practices to protect barn personnel. The traditional intramuscular vaccine route includes the use of needles, which can break, leading to a food safety hazard and damage to the meat, and could be a risk of needle-stick injuries for the person administering the vaccine. These injuries may be exacerbated by the freedom of movement provided in group housing.

Intramuscular vaccines that are administered at the site of invasion – such as the nasal passages, gut and reproductive tract – have the potential to be more effective against pathogens targeting those sites. In addition, a needle-free approach for livestock complements the use of group housing systems. Oral vaccines administered in water or feed are a popular needle-free vaccination route because they are safe to administer and have lower labour costs. Unfortunately, it is frequently difficult to achieve protective immunity through the oral route and control the dose administered to each animal.

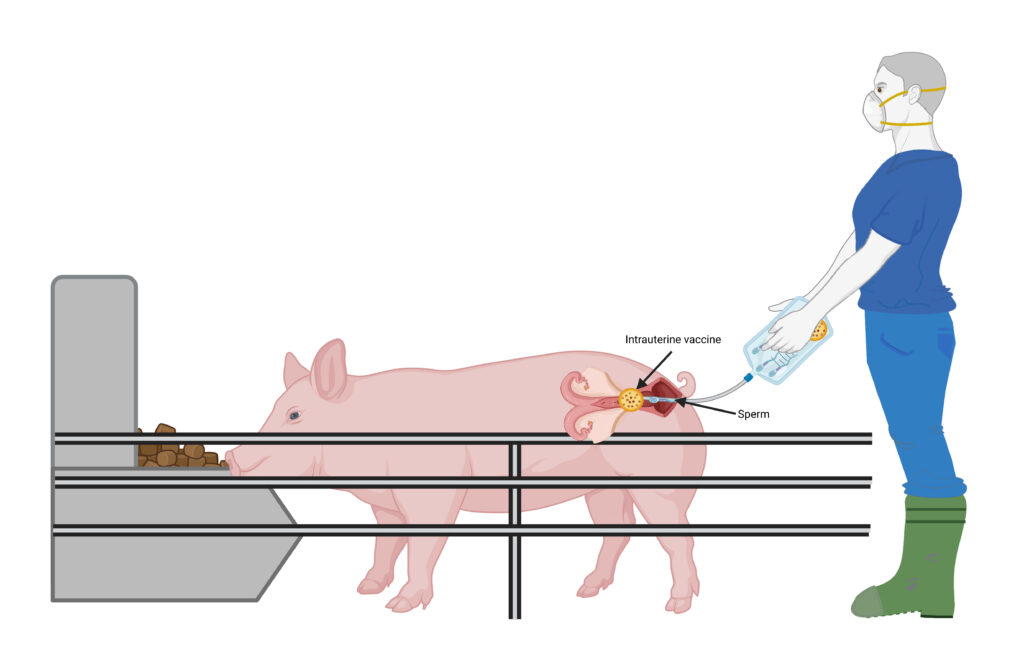

As an alternative, Wilson and her team are investigating intrauterine immunization – administering vaccines directly into the pig uterus during artificial insemination.

“Incorporating vaccination into a current husbandry practice is critical for acceptance by the industry,” said Wilson. “We are trying to develop an alternative, safe and labour-reducing approach that will protect pigs from infectious disease.”

Disease protection could extend beyond PED

Wilson anticipates intrauterine vaccines can protect against reproductive diseases to prevent fetal death and improve the health of the sow, as well as diseases that impact piglet survival after birth. While intrauterine vaccines do not directly immunize fetuses, the sow’s antibodies are passed down to her piglets when they suckle.

Vaccines are carefully formulated so that they do not harm sperm function following insemination or jeopardize sow fertility but instead protect sows against reproductive diseases. Further, by administering the vaccine into the uterus, antibodies are delivered to the piglets through colostrum and milk after the sow farrows. These antibodies can improve piglet health and growth potential by protecting them against neonatal diseases.

The team developed and tested a vaccine against PED, which can cause high rates of piglet mortality. Trial results indicate the intrauterine-vaccinated sows farrowed healthy piglets with no adverse effects on fertility or piglet growth. In addition, the vaccinated sows had significant levels of antibodies against PED in their blood, uterine tissue and colostrum. The colostral antibodies were taken up by the piglets during suckling, and they provided the piglets with a modest level of protection against PED infection.

Wilson and her team are now working on improving the vaccine formulation so that piglets will be fully protected against PED. They are working with collaborators to encapsulate the vaccine with much stronger ingredients to protect semen from degradation. Once the vaccines are delivered to the uterus, they will hopefully trigger a stronger immune response that leads to increased colostral antibodies to protect piglets.

“We have evidence that intrauterine immunization may be an effective alternative route of delivery for vaccines,” said Wilson. “This could be a safer route of immunization that saves on labour without requiring special training to administer.”

The team intends to expand research beyond PED to investigate whether intrauterine immunization can protect suckling piglets against other neonatal diseases, such as those caused by rotavirus and Escherichia coli (E. coli). The approach could also be applied to other livestock industries that use artificial insemination for breeding.