By Andrew Heck

Despite its inherent virtues – from affordability, ease-of-use, nutritional density and taste – Canadian pork has fallen behind the pack when it comes to consumer marketing, compared to its protein competitors. While supply-managed commodities undoubtedly have a financial advantage, it is incumbent upon the Canadian pork industry to keep pace.

Pork demand is largely tied to trends outside of the industry’s control, but that doesn’t mean the industry can’t help influence the trajectory. Consumer marketing has ranked lower on the industry’s priorities in recent years than more pressing concerns, like pricing, which has created an opportunity for increased attention and improvement to current pork promotion efforts.

Once upon a time, Canadians could be counted on to fill their fridges and freezers with fresh and cured pork products, ready-at-hand in a moment’s notice for tonight’s family supper, tomorrow’s bagged lunch or a backyard cookout.

Today, the situation is very different. Consumers are much less inclined to stock up on food at all, as grocery prices have soared and as foodservice options have made meals more convenient than ever. About half of Canada’s nearly 40 million people are under 40-years-old, and nearly 95 per cent of the entire population lives in cities, including many new Canadians. While pork appeals to Canadians of all ages and backgrounds, there’s no doubt that younger, urban, culturally diverse consumers and their children will continue to wield increasing influence over trends.

This societal change represents both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, consumers are much better informed than ever before, and they have a lot more choices when it comes to food. On the other hand, the playing field for marketers has become much more complex to navigate. Pork promotion, however, has been sluggish to adapt.

Pork: the other (non-)white meat

With consumers becoming increasingly health-conscious, and as professional nutrition advice began to steer people away from diets high in saturated fat, pork in the 1980s needed a makeover. The solution? Turning pork into chicken – proverbially speaking – as lighter, bird-based options were rapidly taking flight in terms of purchasing habits.

Marketers readily latched onto this revolutionary idea to modernize pork’s image, beginning with a U.S. National Pork Producers Council (NPPC) campaign in 1987: The Other White Meat®. Thanks to concentrated, well-funded initiatives, the catchy slogan spilled over into Canada, becoming a sentiment that would be adapted and recycled for years. While the tagline was officially retired in 2011, its legacy endures, representing former glory that has yet to be recaptured.

Even though the campaign resonated with a relatively homogenous consumer base back then – using traditional media like print, radio and television advertising, along with point-of-sale activities – it was based on a falsehood, as pork isn’t white meat. In fact, many people eating pork today were not even born when the campaign was conceived.

When the motto first came into use, the positive perception of poultry was hard to ignore. One of the main selling features of fresh pork then, as now, is its similarity to chicken in terms of nutritional value and possible methods of preparation. But does that matter? Fast-forward to the age of the internet, and not all consumers are seeking a chicken copycat anymore, but perhaps one that goes toe-to-toe with a comparable yet pricier protein, like beef.

As chicken consumption has continued to rise in Canada, beef consumption has declined, with pork remaining stable. Logically, filling the void left by beef may hold greater potential than trying to cut into chicken’s popularity, which continues to dominate, almost untouched. Plant- and lab-based meat alternative manufacturers recognized this right away, heading straight for the creation of fake beef burgers. And while these companies have struggled to turn a profit and continue to try their hand at simulated pork, poultry, dairy and seafood products, the soy- or pea-based patty has seen moderate success and commercial application relative to other imitation goods.

When diners are looking for a night out and a satisfying meal, heading to the local steakhouse has remained a popular choice for decades. Even when pork manages to make a prominent appearance on restaurant menus, few establishments treat it with the same level of reverence and respect as beef, and the results speak for themselves, when guests are served an underwhelming, regrettable pork plate.

As these unfortunate eating experiences serve to reinforce consumers’ preferences, beef comes out on top almost every time, which cements in their minds a distinct difference in quality, even if that belief is rooted in a simple matter of technique and presentation.

For a long time, pork was under-classed as subsistence – eaten at home when many people kept backyard pigs for personal consumption or simply didn’t appreciate it fully. Pork’s second-rate historical reputation precedes it, even today, with food safety remaining a common yet dated concern.

Food safety has come a long way over the years, with foodborne illnesses in pork not usually the direct responsibility of production or processing, but cooking. Age-old fears related to Trinchinella bacteria are no longer seen with commercially raised pigs, with other pathogens like E. coli, Salmonella and Listeria now the focus.

As a result, there has been renewed interest and push for health officials to adopt lower temperature standards, given the circumstances around modern pork production and processing. Already back in 2011, the U.S. Department of Agriculture lowered its temperature recommendations for pork to 145 degrees-Fahrenheit, with some rest time, which is consistent with their guidelines for beef and veal. Australian Pork even goes so far as to publish on its website: “Pork doesn’t need to be overcooked to be safe. In fact, pork can be eaten with a hint of pink in the middle.” Health Canada, meanwhile, still places the pork minimum at a stodgy 160 degrees-Fahrenheit, just shy of chicken’s 165-degree threshold.

While it may seem like a reversal of once-trusted marketing strategies, if Canadians – especially the current generation of young and soon-to-be adults – can be convinced to treat pork more like the red meat it actually is, it could showcase the beauty of the product in new ways. Even if a consumer’s preference is to eat out or order in, picking pork could be seen as enjoyable and economical just the same.

Disease provides tangible reason to care

One area in which the Canadian pork industry has a pressing need to brush up is the situation of a potential foreign animal disease outbreak, like African Swine Fever (ASF).

In the event trade comes to a halt due to ASF, pork supplies already in cold storage will become backlogged, awaiting export, which will cause serious supply chain complications. The only immediate reprieve could be renewed consumer interest in buying up the stalled pork until market activities resume as normal. This sounds doable in principle, but in practice, Canadians are nowhere near equipped to eat up much of the surplus.

Flash back to 2003: a case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) was first discovered in Canadian cattle, resulting in the closure of global markets to Canadian beef. In response, the industry rallied Canadian consumers to buy beef… and it worked.

Year-over-year, between 2002 and 2003, per capita domestic beef consumption increased from 13.5 kilograms to 14.2 kilograms. While beef prices plunged as a result of the markets lost from BSE, hurting the industry in the direct aftermath, consumers were thrilled to find deep discounts at retail. Curiously, during that same time, per capita pork consumption declined, with chicken consumption remaining stable.

While Canadian consumers’ response to BSE could serve as an analogy for a hypothetical ASF experience, there are some differences: only about half of all Canadian beef is typically exported, with the other half consumed domestically, whereas pork is undoubtedly more export-reliant. Additionally, romantic stereotypes about beef – think of the picturesque ranching lands featuring cattle and cowboys in the Rocky Mountain foothills – are largely absent with pig production, which positions beef much better than pork among everyday consumers who may view pork neutrally or even negatively. ‘Factory farm’ prejudices are one example.

If ASF were to hit Canada, it is doubtful that Canadians would respond as enthusiastically to pork as they did to beef during the BSE crisis, which means it’s in the pork industry’s best interest to work even harder now to build its brand, before the need becomes critical.

While a supply crisis may be inevitable under ASF, anything helps, when it comes to growing consumption levels. Proactive thinking suggests pork promotion is one way to do it, to develop favourable consumer habits and build pride along the way, which has a ripple effect even when crises are not imminent.

Partners must come together rather than splinter

Today, more than 1.4 million metric tonnes of Canadian pork end up overseas, with around 670,000 metric tonnes being consumed domestically; however, not all pork consumed by Canadians is Canadian. An additional 270,000 metric tonnes of imports – mostly from the U.S. – end up here, highlighting the reality of an integrated, international market, as retailers often choose to sell foreign pork. In foodservice, that can improve profit margins, and in grocery, it may be easier to sell at a lower price, encouraging shoppers’ purchases.

If the proportion of Canadian pork consumed domestically versus exported became even a bit more balanced, it could make all the difference to enhancing Canadian food security and public trust, with a financial benefit to follow for the industry. While private businesses like grocers and restaurants are free to acquire pork from any approved source, it stands to reason that retailers could make the conscientious choice to consider standing behind Canadian versus foreign products. While pork may lack beef’s bold appeal, Canadian consumers are generally on board with the ‘buy local’ mantra, which is a naturally favourable position for the Canadian pork industry.

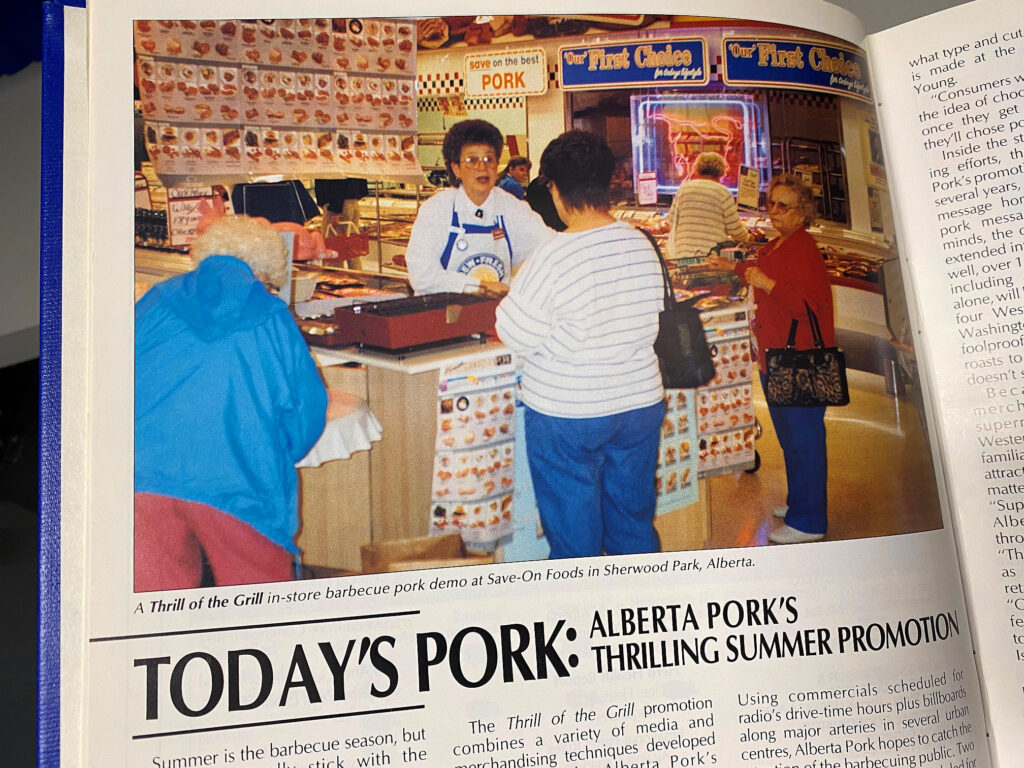

Working with Canada Pork, provincial pork producer organizations across Canada and the Canadian Pork Council (CPC) frequently engage with one another on various promotions, in addition to efforts that take place exclusively at the provincial level. For example, Alberta Pork, Sask Pork and Manitoba Pork join forces regularly to drive initiatives designed for western Canada as a whole, while Ontario Pork and Éleveurs de porcs du Québec (Quebec Pork) have sophisticated programs of their own, tailored to their respective jurisdictions. From having a presence at community events to working with grocers and restaurants to showcase Canadian pork, there is still a place for traditional forms of consumer marketing, although the benefits are typically less impactful compared to decades past. As such, pooling resources for maximum effect, today, possesses the greatest potential.

Through Canada Pork, provincial borders dissolve, and the true face of a united pork front is revealed. To the consumer, it sends a stronger message about the product, through brands like Verified Canadian Pork (VCP), with a value proposition based on quality assurances at the farm and plant level.

From one province to the next, it may be true that subtle differences like feed ingredients, environmental conditions and operational styles contribute to distinctions in the end product, but overall, the average consumer likely can’t tell the difference, may not care and probably doesn’t even know. Suffice to say, marketing at the provincial level, over the national level, divides resources and brings smaller returns than the industry is likely capable of achieving through collective action.

Pork can prevail, but only with fresh thinking

For the Canadian pork industry to address its current marketing stalemate, it has become clear that collaboration and investment are the best way forward. Paired with modern thinking and novel approaches for an ever-changing demographic, pork has more to offer consumers than most other proteins, but those virtues are not as widely appreciated as they could be.

Successful marketing requires data to strengthen its case. If the direct benefits are unable to be measured, stakeholder confidence is lost, and momentum dies. The Canadian pork industry must take action to understand its audience even better.

The changed landscape requires updated tools and tactics to tap into what today’s consumer wants and will ultimately find, with or without industry input. Finding a way to capitalize on the situation remains pork promoters’ Achilles Heel.

If Canadian consumption of pork can tick upward, even a little, it may generate greater domestic interest in this world-leading product, which is the goal that has eluded the industry as society forges ahead faster than pork marketing has been able to match.