By Jette Christensen

Editor’s note: Jette Christensen is Manager, Canada West Swine Health Intelligence Network (CWSHIN). She can be contacted at manager@cwshin.ca.

Blisters are a concerning sight for any hog producer. Some are caused by diseases considered ‘federally reportable’ by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), while some are not. Knowing which is which, and how to protect your herd, is key to managing your barn and protecting the Canadian pork industry at large from potential trade disruptions that could be caused by a federally reportable disease outbreak.

The Canada West Swine Health Intelligence Network (CWSHIN) includes representation from provincial pork producer organizations, swine veterinarians and government officials, aimed at monitoring diseases both absent and present. For CWSHIN, keeping producers informed about the latest disease-related issues across B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba helps ensure the sector is approaching challenges with as much information as possible, to assist decision-making.

Based on CWSHIN’s disease surveillance efforts, we are looking to grow producers’ understanding of blister-related diseases and prepare them to identify and mitigate risks.

Blisters can look similar yet be very different

Five diseases affecting pigs cause blisters that look very much alike: Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD), Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV), Swine Vesicular Disease (SVD), Seneca Valley Virus (SVV) and Vesicular exanthema of Swine (VES). At first glance, clinical signs of these diseases are indistinguishable. Collectively, they are known as viral vesicular diseases. Other diseases like Porcine Parvovirus and Swine pox can also cause blisters, but these are usually identifiable through other signs. Conversely, some blisters are caused by non-infectious exposure.

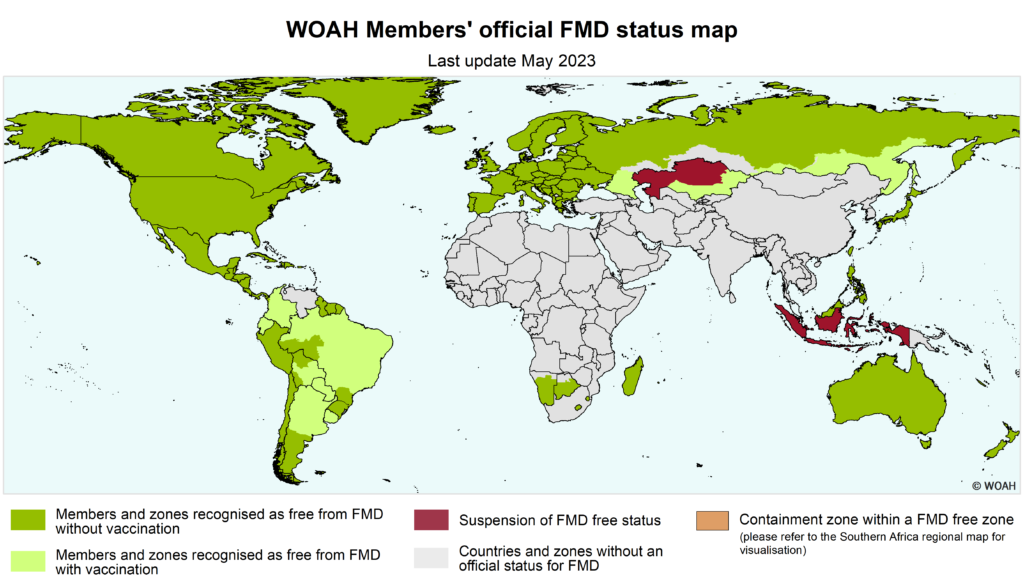

Out of the bunch, FMD is considered the most concerning for surveillance. FMD not only affects pigs but other livestock, such as cattle. The virus can also be carried by animal-based food products, including pork, beef and dairy. Inspection officials in foreign countries receiving shipments of Canadian pigs and pork rightly want to protect their countries from FMD – just like us – which makes this particular disease critical for the industry to prevent.

However, because FMD, VSV and SVD are all federally reportable, when animals in a herd have blisters, the discovery must be reported to CFIA. SVV and VES, on the other hand, are less likely to cause a large-scale disruption to international pig and pork movements.

If a producer notices blisters in the barn, how likely is the cause a reportable disease?

Based on what CWSHIN knows, blisters are least likely to be caused by FMD, as Canada and the U.S. are currently free of this disease. SVV is known to be present in some Canadian and U.S. assembly yards, which makes it a possible diagnosis. However, data from CWSHIN’s surveys show that all cases from 2019 to date have had non-infectious causes, making this the likeliest cause for producers to consider, in most cases.

When diagnosing blisters, there are some challenges. While the specific disease can be ruled out, it is more difficult to find a non-infectious cause and make a definite diagnosis – locating the ‘smoking gun’ as evidence. If CFIA suspects that a blister case is being caused by a reportable disease, restrictions could be placed on the herd until these causes are ruled out.

No matter what, it goes without saying, producers would be wise to take blister cases seriously, working with their herd veterinarians to make informed choices.

SVV-positive shipment causes concern

Last year, a load of cull sows being shipped across the Canada-U.S. border were stopped by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) officials under the suspicion of being infected with FMD. Rather fortunately, testing confirmed that the animals were not FMD-positive but were SVV-positive. While SVV is concerning enough on its own, the discovery of FMD could have been significantly worse. Following this incident, assembly yards in Manitoba were required to step up their disease testing. From these yards, many western Canadian shipments of cull sows head south.

This year, after increased testing, sows with healing blisters were once again seen at assembly yards in Manitoba, traced back to two farms. Testing was able to rule out all viral vesicular diseases for both herds, including SVV and FMD. Due to the presence of blisters, these farms required a thorough investigation.

In these cases, a definitive diagnosis would have been very nice to have, to prevent future cases and repeat investigations at the assembly yards and the farms from where the sows originated; however, with the wide range of potential causes other than viruses, it was not possible to reconcile lab tests with the presence of a cause in the barn. For example, one case had lab findings consistent with chemical or thermal burns, but no chemicals were found in the barn. In the other case, hydrated lime was suspected, but there was no lab test to confirm chemical burn lesions. While we were able to confidently rule out viral vesicular diseases, we weren’t able to find the cause – frustrating, but a good example of why this issue is so complex.

Blister cases such as these are likely to be encountered at assembly yards in the future. If or when that happens, a similar process of investigation will take place. From a producer perspective, you risk blisters being traced back to your herd from assembly yards, and this may cause disruption to your cull sow flow.

As a proactive measure, producers should keep an eye out for blisters in their herds, especially when it comes to cull sows. If you suspect blisters, contact your herd vet, and if the advice is to proceed with ruling out viral vesicular diseases, contact CFIA. Your herd vet can help you work with labs to determine the cause of the blisters. The benefit to the entire industry is that, every time viral vesicular diseases are ruled out, we have more evidence of freedom from reportable diseases like FMD.

Reportable diseases unlikely to be present

CWSHIN’s collaborative approach to disease issues provides benefits to the entire Canadian pork industry. When it comes to disease surveillance, we are working hard to continue to help provide evidence that Canadian pigs are free of diseases that could halt international trade. As producers know, disruptions to the pig and pork value chain have a ripple effect that can hit home fast.

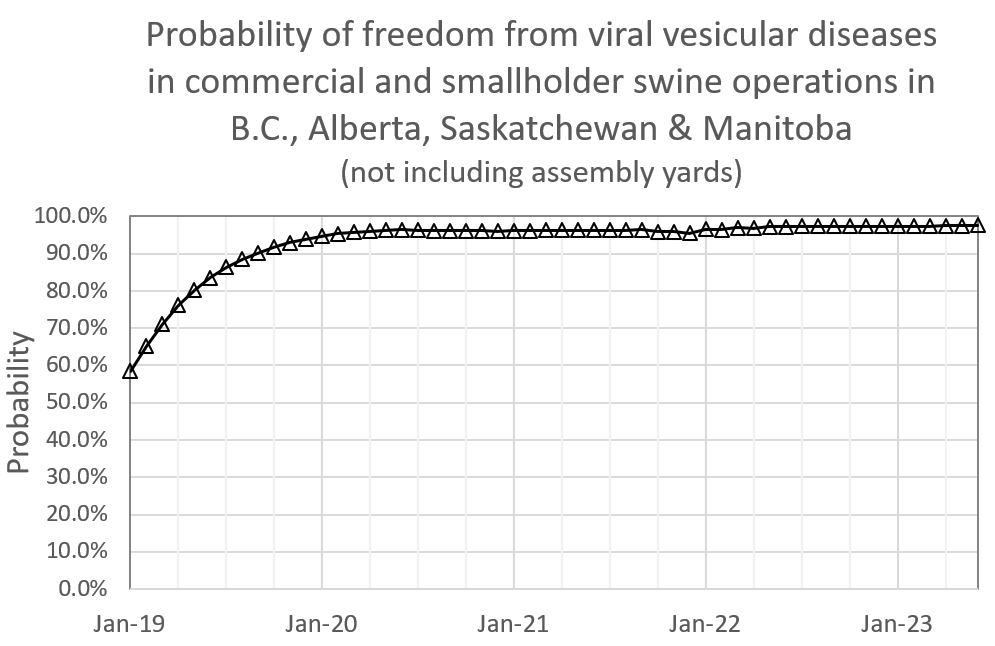

Since 2019, CWSHIN stakeholders have participated in quarterly surveys that rely on clinical impressions to gauge the risk of finding viral vesicular diseases in western Canadian herds. Based on the information from the surveys, CWSHIN maintains a model that calculates the probability of freedom from exactly these diseases. Currently, the probability of freedom is about 96 per cent, which is as high as it can get, considering that no disease is ever completely risk-free from being introduced.

Enhanced biosecurity measures and diligence with assessing animal health are critical steps for disease prevention. CWSHIN is here to be a resource for producers, should there be any question about the health of Canadian pigs.